“Niche filmmaking” is a term that’s been somewhat tainted by its overuse on the business side of the movie industry. Young filmmakers are now urged to not only find their niche, but even their “super-niche,” when considering how to market their talent—and find their talent a market.

Artistically, most of the best documentaries—perhaps all of them—can be considered niche filmmaking. These films take people, places and things that may be little-known or even completely unknown in mainstream culture, and make a case for why an audience should spend 90 minutes or so getting to know and hopefully understand them.

But first, the filmmakers themselves have to spend far more time—weeks, months, even years—doing the same thing. And in that time, the filmmaking process can get awfully complicated. As documentarian and subject bond, and sometimes become friends, the fact that in the end the filmmaker will be putting the subject’s story up on the big screen for the world to see can become significantly more nerve-wracking. Sure, the fact that they are telling the story in the first place might bank them some goodwill, but ultimately there is a very real possibility that a documentary subject may see his or her story very differently.

This year’s Santa Cruz Film Festival offers the chance to look at that dynamic on a number of different levels.

“I think the films this year deal with that—doing justice to your subject in bringing it to the world,” says Logan Walker, the festival’s head of programming.

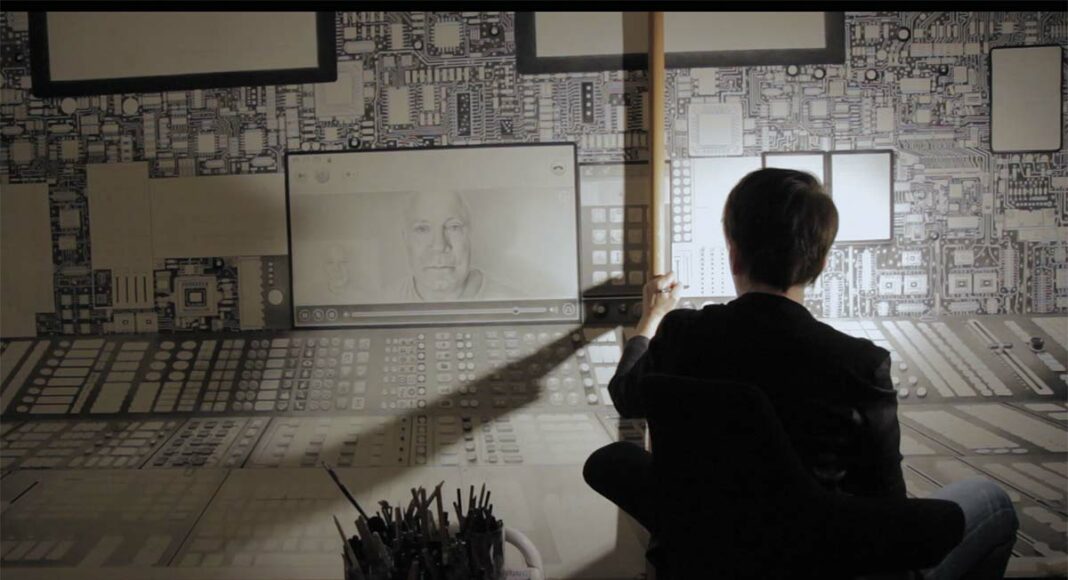

It’s a particularly good year to examine this deeper question of documentary ethics and aesthetics, since many of the documentaries at this year’s SCFF are themselves about visual art and artists who create representations and reflections of culture, including James Scott’s Love Bite: Laurie Lipton and Her Disturbing Black and White Drawings, Betsy Andersen’s Eduardo Carrillo: A Life of Engagement and Tadashi Nakamura’s Mele Murals. Other films focus on sonic art, like Michael Coleman and Emmanuel Moran’s The Art of Listening, and Patrick Shen’s In Pursuit of Silence.

“This year we got a lot of amazing films that are about art and about sound,” says Walker.

Other films at the festival deal with subcultures that may be particularly wary of how they’ll be represented on film, like Pedro Delbrey’s Santa Cruz-set Pussywillow Dirtbags, Kami Chisholm’s Pride Denied and Kurt Vincent’s The Lost Arcade.

I talked with the filmmakers behind five of these films to get a better understanding of how they dealt with the unique challenges that came with their chosen subjects.

‘LOVE BITE’

James Scott spends most of his working life editing other people’s documentary films, and the ethics of how to fairly represent a film’s subject isn’t just a question, it’s the question.

“That’s what we think about every day, all day,” says Scott. “It’s such an ethical and moral responsibility to tell someone’s truest story.”

But when it came to his directorial debut Love Bite: Laurie Lipton and Her Disturbing Black and White Drawings, the question got more personal than he could have foreseen. Scott, a native Canadian who now lives in England, came across a book about Lipton’s work in a head shop in Winnipeg. The first drawing that appears in the film is the one that first magnetized him.

“I was gobsmacked,” he says. “I don’t get moved emotionally or politically by many other artists. But there’s something about what she’s doing that crosses all races, creeds and religions. To me, that’s something only the Old Masters were able to do.”

As he dug deeper into Lipton’s somewhat mysterious 50-year history of making art, he was shocked to find almost no information about her online, and over time the process of making the film became a personal crusade.

“I felt like it was an injustice that Damien Hirst is selling his polka dots for a million dollars, and here’s Laurie locked away in her room,” he says.

Ultimately, he spent four and a half years getting to know Lipton and documenting her story.

“In that time, Laurie and I built up quite a friendship,” he says. “That changes quite a lot, in terms of how much she was willing to tell me.”

That’s especially evident in the last scene of the film, which contains a rather shocking reveal from the artist. It was also the very last footage he shot for the film. “It took four and a half years for her to trust me enough to tell me that,” Scott says.

And it only added to Scott’s anxiety over what Lipton would think of how he represented her art and her very personal story. “It was a huge amount of pressure,” he says.

However, when Lipton saw the final version at a South By Southwest screening, Scott was able to breathe easy. “She’s happy,” he says, “and that makes me happy.”

‘PUSSYWILLOW DIRTBAGS’

There’s getting involved with your documentary subject, and then there’s getting involved with your documentary subject. Pedro Delbrey most definitely did the latter when he played for two seasons with the group of Santa Cruz baseballers whose stories he would go on to document in Pussywillow Dirtbags. The thing is, he didn’t actually know he’d end up making a movie about them.

“I didn’t start out with the intention of making a film,” says Delbrey.

At the time, he was finishing film school at UCSC, and looking for a project. The baseball games every Tuesday at Harvey West Park were just a way to blow off steam. In fact, when he first decided to make a film about them, even the guys he was playing with expressed disbelief. We understand why you’d want to make a baseball movie, they told him, but why us?

The reason, says Delbrey, is that he saw a universal appeal in their love of the game.

“The subject of baseball, the subject of nostalgia, reconnecting with childhood dreams, I think a lot of people can connect with that,” he says.

However, his closeness to his subjects did make the special screening he did for them at the Rio Theatre—before he showed it to other audiences—more harrowing.

“You get really close to these people, and they let you into their lives. Then you weave the story as you see it, and that may not be a valid representation in their eyes,” he says.

In the end, “I got their blessing, which made me feel a lot better,” says Delbrey. “But that said, I don’t think [the subject’s approval] is necessarily a prerequisite.”

‘THE LOST ARCADE’

Neither Kurt Vincent, director of The Lost Arcade, nor Irene Chin, the film’s producer, consider themselves gamers. But when they started making a documentary about Chinatown Fair, the last video game arcade in New York City, they got so into the minutiae of gaming subculture that it started to reshape the film itself—and not in a good way.

“We realized we were making a movie that would only connect with the people who shared our interest in these weird details,” says Vincent. “Once we realized ‘this isn’t about the nuts and bolts of Street Fighter,’ that’s when our approach really started working.”

Instead, they went for a “more human and personal level,” says Vincent, and focused on what made people dedicate their lives to the subculture. As the interviews got more revealing, Vincent began to feel more and more protective of the interviewees.

“I spent many years making this movie, and I’m sure there were times when they were like, ‘Are we wasting our time trusting this guy with our secrets?’” he says. “That was a specter hanging over the whole editing of the film. These people are real to me. They’re not just subjects. We got to know each other really well.”

Because of that, Vincent says he was “so nervous” at the New York screening of the film, and incredibly relieved when one of the key people in the story, Akuma Hokura, came up immediately afterward and gave him a big hug.

“He bared his soul to us,” says Vincent. “He gave us a piece of himself.”

‘THE ART OF LISTENING’

“People are giving you their time, but more than that, they’re giving you their voice,” says Emmanuel Moran, co-director of The Art of Listening. “That’s definitely a challenge in making documentaries.”

It’s an interesting way to put it, since The Art of Listening is actually about voice, and other types of sound. It’s an in-depth look at how we hear music, and the complexities of our relationship with it.

“So many times people take sound at face value, and they don’t really understand how it gets to us,” says co-director Michael Coleman. “But as a listener, you’re just as involved in the music creation process as the artist. We wanted to show the value of having a closer relationship with music.”

Coleman says that of some 200 interviews, only 45 were ultimately used, and that he and Moran were “so careful and protective of the people in the film, and how we represented them.” In terms of winning their subjects’ trust, though, they had a leg up: they were often talking to audio engineers who are generally sought out for their understanding of sonic science, and not for their deep love of music.

“People don’t ask them about the emotional part of music,” says Moran. “But they’re some of the most passionate people in the music business.”

It also helped that both directors had a background in music production and could converse at a knowledgeable level with their interviewees, who were often just as interested in dispelling misconceptions about the music experience as Coleman and Moran are.

“They were attracted to what our intent was,” says Coleman.

‘IN PURSUIT OF SILENCE’

In a way, the flip side of The Art of Listening is In Pursuit of Silence, which sent its filmmakers around the globe in pursuit of explaining the power of silence. They shot in eight countries, and went everywhere from the anechoic chamber at Orfield Labs in Minneapolis, said to be the quietest place on Earth, to Denali National Park in Alaska to the Urasenke Tea House in Kyoto, Japan, to Trappist and Zen monasteries. And though the highly meditative film—which the Austin Chronicle’s Wayne Alan Brenner compared to the groundbreaking Koyaanisquatsi, does feature interviews, the filmmakers felt they had to think about being true to their subject in a radical way.

“The main character in the film is silence,” says the film’s producer, Brandon Vedder. “What we had to do was try to understand the power of silence in our lives. A lot of people fall into this point of view that silence is the lack of something. But this is one of the more mystic and spiritual opportunities we have on a daily basis. It’s a bedrock of life.”

To extend the metaphor further, the film’s villain could be said to be noise. “Noise pollution is only second to air pollution in terms of harmful effects on the human body,” he says. “It takes an incredible amount of energy to filter out all this unwanted noise.”

One aspect of the film that will undoubtedly intrigue many viewers is its opening examination of John Cage’s famous experimental piece “4’33,” which is four minutes and 33 seconds of silence. The filmmakers were already working on In Pursuit of Silence when they discovered Cage’s controversial work, and set out to tell the story behind it.

“We realized that his journey from being known as this crazy noise musician to silence was a fascinating way to explore this,” says Vedder.

The final cut is what he describes as “a kaleidoscopic view on silence. The film is really, really experiential. It can be overwhelming to a certain extent. You can’t just be a passive observer.”

SCFF at the Tannery

June 1-5

This year’s Santa Cruz Film Festival will be presented primarily at the Tannery Arts Center, where there will be three different screening venues. Logan Walker, head of programming for SCFF, anticipates a lot of energy swirling through and around the festival as it runs concurrently with the Tannery’s Thursday Art Market, as well as First Friday, and the Santa Cruz Pride festivities on Saturday, June 5.

“It’s going to be a very festive atmosphere,” says Walker. “I think it’s going to be great that we’ll be on this campus where you can walk from theater to theater.”

Catherine Segurson, best known locally for producing the Catamaran Literary Reader, took over as director of SCFF this year.

“She’s been great at going out and making things happen for the festival,” says Walker, who’s in his third year as SCFF programmer.

The festival will kick off at 7:30 p.m. on Wednesday, June 1, at the Del Mar with The Anthropologist, a documentary about anthropologists Margaret Mead and Susie Crate, as told from the perspectives of their daughters.

The Closing Night Party will be at 9:15 p.m. on Sunday, June 5, at the Radius Gallery.

For a full schedule of films, and to purchase festival tickets and passes, go to santacruzfilmfestival.org.

— Steve Palopoli