Joseph Clements, the former singer for the punk band Fury 66, has dedicated himself to teaching mindfulness meditationto the most at-risk populations in Santa Cruz. Leading groups in rehab, and lock-up, Clements has become the teacher that he never had. Not one to want to ever “get stuck in the muck” of his personal story, Clement’s tale is fraught with the perils of addiction. It’s a cautionary tale with a constantly evolving happy ending.

“I think so many people feel ‘lesser than.’ What do you do with that information when you believe it is true,” asks Clements. “I think the root of it is, not feeling like you belong to anything or anyone. It’s a survival instinct of our species to want to belong to a bigger group for safety. It’s how we survived. If we belonged, and there was a Saber-toothed tiger, we had each other’s back. If you don’t get that at an early age in your household or immediate environment, you feel less than. And then you carry that out into society,” says Clements.

He’s had many success stories, including writer, music seller and bar keep Mat Weir.

“I’ve been a part of the Santa Cruz Meditation Group from the ground up,” says Weir. “Not only does it provide me a solitary place to explore the true nature of my thoughts, emotions and actions, it provides me with a weekly community of like-minded friends.

“Through one of his own teachings, or one from his diverse guest speakers, every session I’ve been to has provided me personal insight and a greater sense of connection. While you’ll hear him use terms like Dharma or Sangha, Joe likes to lovingly describe the group as Buddh-ish not Buddhist, keeping the door open and welcoming to anyone who wants to walk in.

“The diversity of the group helps make it so special. Young and old, non-binary, queer, bipoc , tattooed, punks, hippies and normies all congregate together for 90 minutes of connection, peace and insight. Being ‘hella meditated’ is the new hardcore. ”

“Love says I am everything. Wisdom says I am nothing. Somewhere in between the two, my life flows.” – Nisargadatta Maharaj

Sit. Feel. Heal. Bagel.

Clements, from the top: “I was born in Dominican Hospital. My parents are Valley kids, who grew up in Boulder Creek,” says Clements, the uber-chill, rock father, meditation facilitator.

With clear, lucid, weary, eyes, and a healthy glow, Clements has an intense ability to listen – which isn’t easy to do. We are at The Bagelry on Cedar Street, at noon, during the school week. The world is in motion around us, but the vibe at our outdoor table is peaceful. It feels like I’ve been placed in the Cone of Silence. Clements begins with his origin story.

“When I was born my dad was 17 and my mom was 18,” Clements says. “I was a product of some wild shit. When I was 1, my grandparents lived right next to the Venetian in Capitola. And we lived there for a year.” But it was on 26th Avenue that Clements, and his young parents, finally settled. “I grew up there, and never left. I’m 53, and was born in 1970,” Clements adds, for the record.

Clements’ father was a commercial fisherman and during the off-season, would work the fish counter on the Wharf. His mom worked in a frozen food packaging plant. They were teenagers, trying to make a living, while raising three young children, two blocks from the ocean.

One thing Clements definitely recalls is the parties at his home on 26th Ave. Zeppelin, Skynyrd and Sabbath blasted all night long. “When things would get rowdy in the house, I’d get as close as I could to the mesh-covered speakers and feel them vibrate around me in the air, and rumble the floor beneath me,” says Clements.

Through music, the young Clements was able to feel like he was still part of the party, but separate enough to feel safe. “Music, from the beginning, has always reminded me of community and ease. Especially when it’s loud and played just a little aggressive.

“The surf/skate culture that I grew up in had a clear line between East Side and West Side. I was an East Sider and I wouldn’t come down to the West Side –especially, not to surf. We would go to Derby Skate Park (the oldest public skate park in North America) to skate. When it came to punk shows, we had a hub called Club Culture,” says Clements.

Opened in 1984, the notorious club was centered at 418 Front St. Club Culture was the vibrant vision of Richard Walker, who had changed the goal lines for where music was heading in Santa Cruz with his band Public Enemies (later called Child Prostitutes). It was an all-age venue and a beacon, like a giant screaming hand, to every misplaced youth in the county.

“My first punk show there was like, ’86 with Faction, JFA and Caustic Notions, or something like that,” says Clements. “It was bonkers. We did a bunch of acid with a friend, drank a 40 ozer and went to the show. I just thought the whole time, ‘What the hell is this.’”

What separated Santa Cruz from other scenes in America, was the cutting edge lifestyle. “I went between surfing and skating, but I stuck with skateboarding a little bit more,” he says. For the young Clements, it was easier just to grab his deck and hit the street.

During Clements formative years, Santa Cruz was already known worldwide as a haven for surfers – a destination point for those who would rather be in the ocean. In 1986, when Clements was 16, the Santa Cruz Surfing Museum at Steamer Lane, opened. The museum was dedicated to “All youths whose lives, through fear of misadventure, are terminated before realizing their true potential.”

It was not only the waves that could end a young life, but also, the drugs, alcohol and gang-like mentality.

“There was a localism in this town, and this pride, that kept people from being well-rounded and open-minded. The vibe of surfers, while I was growing up, was kind of angry,” he says. As the popularity of our surf town grew, things became very territorial.

You can almost see the confrontations that ensued in the mind’s eye. Words yelled out. Fists thrown. Probably more than fists. A melee of surfboards and beer. This ain’t Gidget.

Breath. Here. Now.

But I’m in the here and now and safe, still at the Bagelry. The commotion has settled down around us– the high schoolers have left. Clements is very careful in talking about how things are different today. “It’s not that way anymore. And I don’t want to stereotype or pigeonhole anybody, but the localism kept people from growing. I was caught up in it. I had a deep need to fit in– which became problematic, in a lot of ways. Ultimately it becomes about ego and identity.”

Without a tight family structure to plug into, or any scene that was uplifting and supportive, Clements turned to vices that were wickedly easy to obtain.

Drugs were around every park bench. Education about substance abuse was still dripping slowly out of Reagans, “Just Say No,” hypocritical agenda. With little adult supervision, Clements’ mom did the best she could. One thing, led to another. “I started smoking weed when I was 12, and this is difficult to talk about, because my kid is 12,” says Clements.

I can tell the story is about to shift. I’m glad the high school kids have left. Or maybe they should have stayed. Maybe this is the exact kind of story that a young Clements could have stood to hear. Or perhaps, this is the time-traveler moment, where Clements admits that he figured out a way to hijack the slipstream to become the voice that he needed to hear the most.

“By the time I got to my 20s, I was done,” says Clements. “I was strung out on heroin and all kinds of other shit. I was living out of my car and it was a bad scene. I was trying to get clean and sober. The last time I tried to detox, and got out of rehab, I went to the West Side where there was a 12-Step Fellowship. And, I stayed. Because I was living on the West Side, none of my friends saw me on the street. I found a really cool group of young people, also in recovery, who were into punk and skateboarding and it was pretty cool.”

Clements keep going to meetings and hanging out with like-minded sober people. And then, the devilish mistress, music, entranced him.

“Music really saved me in the early days, and then destroyed me, in the same way,” Clements admits.

“I never felt like I was a part of anything,” says Clements. “I always felt lesser than. Then my ego would come in with the surfer dude/punker attitude of, ‘I’m better than you.’ I was either lesser than you, or better than you. But most of the time, it was lesser. Even in the punk and skateboarder realm, I never thought I was good enough.”

Finally sober, Clements launched his career in music. After his first performance singing with his band Schlep, up in the Santa Cruz Mountains, Clements felt peace, ease, connection and validation. Chasing the performance high became his new drug of choice. In the summer of ’93, Clements was contacted by Russ Rankin from the band Good Riddance, he was looking for a singer, and Fury 66 was born.

There’s an entire book that should be written about Fury 66. The rise and the descent of the band, is a wild, enthralling, furious ride. But to the point, even “fame” didn’t fill the pit in Clements’ soul.

Fury 66 was gone and without the gusto and validation of being onstage, the “I’m not good enough” army returned en masse. That early psychic trauma had never really been healed. At best, it had been bandaged.

Clements was still working in the music industry at Sessions Records, happily married to the love of his life, and had just built his own dream recording studio, Compound Records. But the unresolved nagging doubt of not fitting in, led Clements back down a desperate, dire, spiral into the void.

For Clements, it was the discovery of mindful meditation that gave him direction, a path forward, and a language that resonated at a cellular level. In the cyclical nature of Santa Cruz magic, it was the old friend who went with Clements to Club Culture, who himself found sobriety, and invited him to a weekend workshop at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur. Clements took meditation, “one breath a time,” and found that it steered away his attention from anger, stress and frustration.

“I learned to sit in the fire of fear, watch the anger wash away the sadness of my tears, and found freedom in the ashes of my suffering.” – Joseph Clements

When Clements talks about his journey, it’s easy to see the same scenario being played out with millions of people. We all know, or are, the sensitive kid who had to hide their sensitivity, because, it’s scary to be sensitive. Everyone knows someone, or is, that person who turned to drugs and alcohol to create that thick skin, that keeps one from feeling anything.

“I’ve known Joe since the 1980s,” says Clifford Dinsmore, the lead singer of Bl’ast!. “We lived in a neighborhood we called The Devil’s Triangle. It was a constant orbit of debauchery. The entire scene was in contrast to the hippie vibe that Santa Cruz was known for, until that point. We were a very close-knit community.

The sharing was seriously missed during the pandemic.

“This is my sangha, my community, and when I step through the door on a Thursday night, it is my sanctuary,” says Heather Duffy, an instructor with the Santa Cruz Poetry Project. “During the pandemic I had a home routine but I missed sitting with other meditators, and I wanted that sense of showing up for both myself and for others. It’s a simple and powerful practice, and I love the chance to slow down and breathe. I don’t have to do anything for just a little while, I can just be, and I don’t need to be perfect. My mind will do what it does. Whatever is going on with me is held with such gentleness and kindness, no judgment or solving.”

For Clements, the journey is a constant challenge.

“I’m still continuing my own inner journey and teaching people the mindfulness meditation and emotional understanding tools that helped me get to where I am today,” says Clements. Currently working with incarcerated youth, and other people who suffer from addiction, he wants to help anyone that “wants to be free from the tyranny of self.” Clements continues his self-exploration, while helping as many others as he possibly can through things like The Santa Cruz Meditation Group at 7pm every Thursday night at the Veterans Hall.

“When the resentment kind of lifted, for me, is when I began to have empathy for my parents. They were teenagers raising a baby. They were doing the best they could,” says Clements.

When you talk about forgiveness, the hardest forgiveness is the forgiveness of ourselves. “It’s almost like I’m re-parenting myself. There’s that little kid that’s still in there. So I’m showing up for that little kid asking for forgiveness – forgiveness for me, for turning my back on him. I got to meet that wounded part with wisdom and compassion. And that, actually, was where the healing began.”

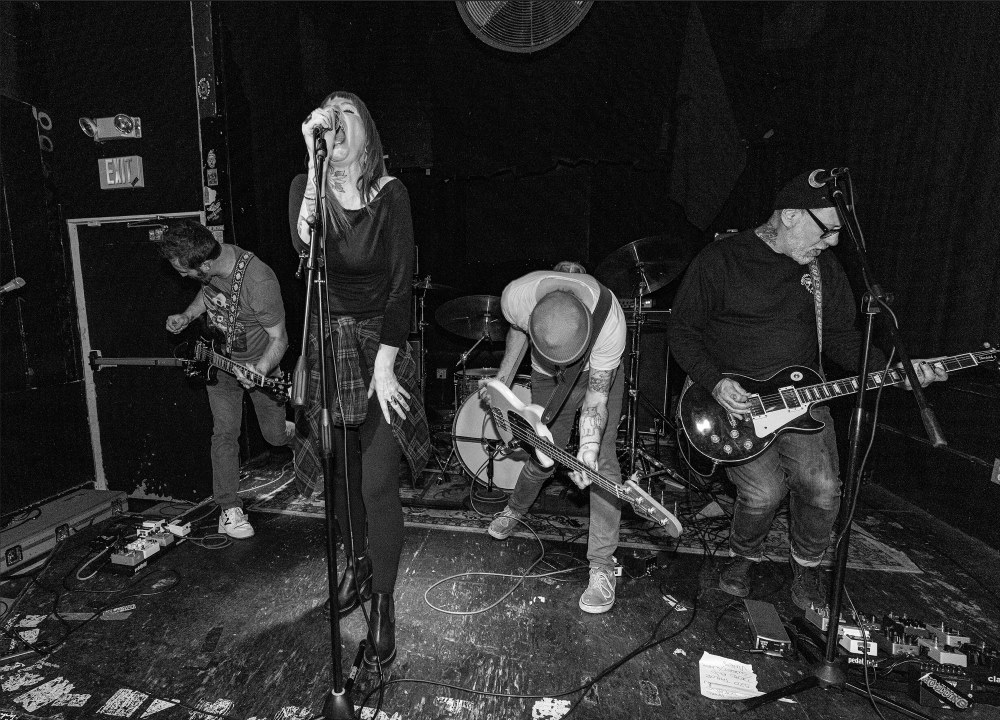

To find out more about Joe Clements and where to attend a meditation class, retreat, personal coaching, or podcast, go to josephclements.com Also, checkout Clements new band HOTLUNG on May 4th at The Blue Lagoon