In 2015, protestors took to the streets across the country demanding an end to police brutality amid several high-profile cases where police killed unarmed Black men and got little more than a slap on the wrist. That July, the Movement for Black Lives held its first conference at Cleveland State University—just a few miles from the recreation center where a Cleveland police officer killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice the year before—to discuss how to hold law enforcement accountable for these actions.

After leaving the conference one afternoon, several attendees witnessed a 14-year-old boy at a nearby bus stop being harassed by police, who believed he had an open container of alcohol. When they confronted the officers, they were pepper-sprayed, but they stood their ground and were able to get the boy’s mom on the phone and later on the scene. She demanded the police release her child. To everyone’s amazement, they did.

In what felt like a rare win against the police, the crowd of 200 spontaneously chanted the chorus to Kendrick Lamar’s recently released song, “Alright”: “We gon’ be alright! We gon’ be alright.”

Author Marcus J. Moore writes about this moment in his upcoming book The Butterfly Effect: How Kendrick Lamar Ignited the Soul of Black America, which will be released on Oct. 13.

“It was a heroic scene, a sea of triumphant Black people walking through the streets, passing police cruisers like they weren’t even there,” he writes in the book. “The Cleveland demonstration was a flash point for the movement overall, and now it had an anthem.”

“Alright,” arguably one of the most important songs of the decade, was inspired by Lamar’s trip to South Africa, where he witnessed extreme poverty, but also resiliency. The song’s lyrics confront police brutality with visceral ferocity and anger, while Lamar weaves in his own story about battling the dark temptations of fame and greed. The chorus offers a sliver of hope, or at least suggests the will to endure when things seem to be at their worst. It resonated strongly with listeners when it was released on his 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly.

“It’s a personal song that became a protest song because of the public,” Moore tells me. “You barely heard it on the radio, but the fact that you hear it in the street is more validation for him. In that way it became a protest song because you had all these Black people who took ownership of it. It became their ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing.’”

Ayo Banjo, a community organizer and UCSC Student Union Assembly president who has been central to the recent Black Lives Matter protests in Santa Cruz, says that Lamar’s music has been influential and inspirational to his own activism. He agrees that “Alright” captured an important moment in time.

“‘Alright’ is an anthem. It’s still an anthem, and it will continue to be an anthem,” Banjo says. “The song captures the struggle of resiliency. How hard it is sometimes to continue forward even when you feel like there’s no hope. Even when you see another Black death in the media. The mantra itself represents the resiliency of Black America. The song emulates the same grit of folks that fought so hard for civil rights. Those same people that are relying on our generation to pick up the mantle and carry that same optimism and hope for the future, to envision a new reality.”

“Alright” was only one of many times Lamar’s music has impacted culture over the past decade, as Moore’s book documents.

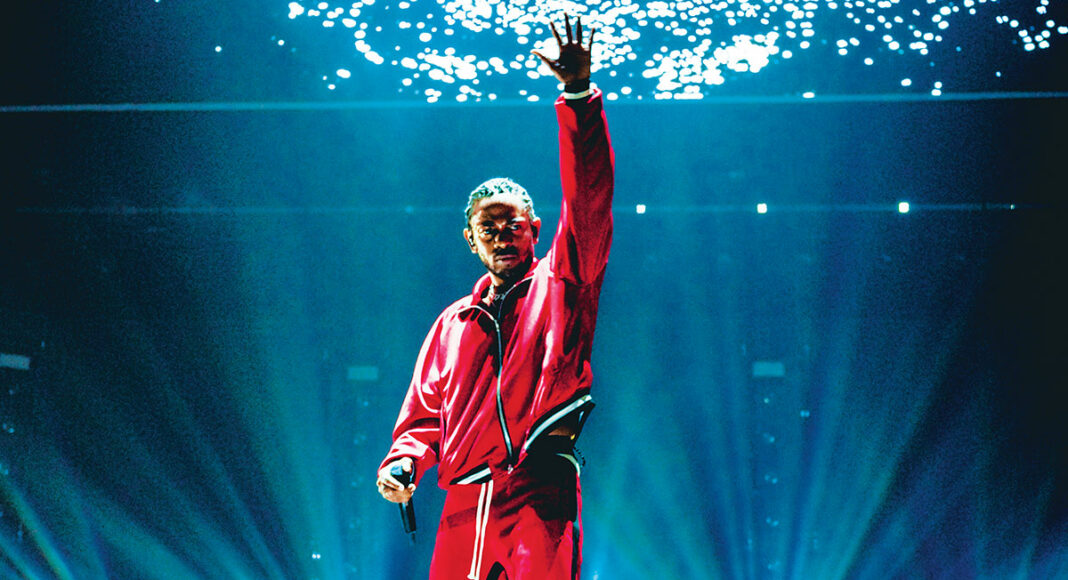

Another critical moment came six months after the Cleveland incident, when Lamar delivered one of the best, most provocative Grammy performances ever. He and his crew shuffled silently on stage in prison chains, demanding the audience digest the meaning behind this powerful image: This country treats Black men like criminals. He performed an incredible and theatrical medley of “The Blacker the Berry,” “Alright,” and some previously unreleased material, fueled by tumultuous live jazz and closing with the evocative image of a map of Africa and the word “Compton” written on it. His performance spoke to the complex issues of Black identity, intergenerational trauma and radical joy with the emotionality and nuance it required. And people from all walks of life were paying attention.

“When you think of the Grammy audience, you’re not thinking of a room full of Black people. You’re thinking about white people who probably barely know who he is,” Moore says. “For him to make that bold statement, along with To Pimp a Butterfly, I think that’s what sort of pushed him into pop canon. It was fearless and it was bold.”

Changing the Game

The Butterfly Effect documents Lamar’s life and career, focusing on the historical and cultural context and on Lamar’s importance, which Moore argues has already been significant, despite Lamar still being only 33 years old, and with likely many more albums to come.

“I think he is the greatest rapper of his generation,” Moore says. “I feel like the reason that people cling on to him is because he gives his listeners something to dive into that makes them realize that everything is going to be okay as long as you’re honest with yourself.”

Nearly every rapper big or small has respect for Lamar. He’s one of the few rappers who has somehow kept his indie cred while gaining mainstream acceptance. Santa Cruz rapper Alwa Gordon says that Lamar is an entirely unique figure in mainstream hip-hop.

“He’s brought lyricism back,” Gordon says. “I think his contribution has been making sure that artists understand that they can be commercially successful, while at the same time not straying from the message. His message has always been the same. It’s always been about the struggle. It’s always been about Black empowerment. It’s always been about the streets and for the streets. Elevating people actually talking about real shit.”

Moore first conceived his book in 2017. He was walking around in Brooklyn, on his lunch break, listening to the jazz-infused To Pimp A Butterfly and marveling at how relevant the album still was. He initially thought it would be great to write a book about the album, which he considered a game-changer for hip-hop both musically and thematically. But as the project evolved, Moore expanded the book’s scope to include Lamar’s entire career.

There was a lot to cover. To mainstream listeners, Lamar seemed to come out of nowhere with To Pimp A Butterfly, but he had actually worked his way up for years, grinding in the underground L.A. scene. Before he released anything under his own name, he put out four mixtapes under the name K-Dot. His rapping was superb, but the emotional complexity, vulnerability and high conceptual approach to hip-hop wasn’t really there yet.

He released his first full-length album Section.80 in 2011 under his own name. It was an underground hit that made a lot of fans and critics take notice, but it was his next album, 2012’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City that shot him into hip-hop stardom. The record yielded the singles “Poetic Justice,” “Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe,” and “Swimming Pools (Drank).”

Good Kid went platinum, but the legacy of the record, Moore argues, is much greater than radio plays and record sales. Lamar was able to shed much of his early rapper persona and tell an out-of-sequence, intimate autobiographical story that flows like a movie. The album addresses the contradiction of being a child in an environment with gang violence and police brutality that innately strips you of your childhood innocence. He talks about the grounding role of familial support and the hurdles of intergenerational struggle, while also humanizing the characters in sympathetic ways. He implores kids in similar situations to dream beyond their circumstances.

Good Kid, M.A.A.D City was one of the Lamar’s most straightforward hip-hop records musically, which resonated hard with rap music fanatics, but it also showed the depth to which Lamar could take personal lyrics, carefully paced interludes, relatable characters and larger universal truths to craft a succinct narrative.

“Good Kid is definitely the hip-hop head album. People who love Nas’ Illmatic loved Good Kid because he’s an adept storyteller,” Moore says. “Good Kid, M.A.A.D City was important because that was his coming out moment.”

Black and Proud

To Pimp A Butterfly (2015) was next and was like nothing before it. It was provocative. It was filled with spoken word and jazz. It was a dense and long album that had nothing to do with what was popular in hip-hop or pop music at the time. It was even a bit overwhelming and required repeated listens to fully unpack, but it was rewarding for anyone who took the time. And despite what a superb artistic achievement it was, it was a hit among a wide-ranging audience.

It was also unapologetically Black. Lamar knew that he was creating his masterpiece and wanted to work with the best musicians, linking players from different scenes. He brought together musicians like Thundercat, Terrace Martin, Robert Glasper, Kamasi Washington and Flying Lotus. It was a lengthy process—and, remarkably, the jazz element didn’t come together until the final stages.

“That is definitely the one that broke him through, and people realized, ‘Oh who’s this dude who’s doing this really wild crazy music?” Moore says. “That tapped into the old jazz heads from L.A. and New York. They’re like, ‘This kid, he operates like a jazz kid. He’s thinking about scales and things of that nature. He tapped into the music nerds. He had love from the gangs in Compton. And he had love from older people, younger people. Everybody could see the musicality, and they loved the story.”

To Pimp A Butterfly gave voice to the struggle and triumphs of Black America, but it also helped usher in a new resurgence of jazz music. Post-Butterfly, people weren’t just crate-digging for classic jazz records. New jazz artists were suddenly getting the kind of acclaim and attention that no one in the genre could have anticipated a year earlier, like adventurous jazz saxophonist Kamasi Washington, who subsequently released the experimental triple album The Epic to a sizable audience.

Lamar had a lot to say on To Pimp A Butterfly. His trip to South Africa before the album had changed him in a lot of ways, and he saw connections between Africa and Compton, and his own struggles as a newly famous musician. He blended it all together in a compelling way that was both urgent and philosophical.

“That is his kitchen-sink record. To add all of these layers on top of it, he wanted to tap into L.A. jazz history. He wanted to tap into the city’s soul. But he also wanted to discuss how South Africa affected him,” Moore says. “That’s the one, even if you listen to it now, there’s so many different things going on. You have the spoken word poem that’s woven throughout.”

After To Pimp A Butterfly, Lamar released Untitled, Unmastered (2016), compiling unused early demo tracks from the To Pimp A Butterfly sessions. He later released Damn (2017) and curated the soundtrack for Black Panther (2018). Damn was a huge force in pop culture. By the time he’d released it, people were ready to dissect every word Lamar was spitting.

Damn made some pretty strong, angry statements in the early Trump years, when many people of color felt betrayed by their country for electing a president who failed to condemn—and perhaps even straight-up supported—white supremacists. On the lead single “DNA,” in-between virtuosic verses about the complexity of the Black experience in the U.S., he samples a 2015 clip of Geraldo Rivera from Fox News criticizing Lamar and hip-hop in general for doing “more damage to young African-Americans than racism in recent years”—a particularly tone-deaf statement as the country watched the rise of hate crimes and thousands of people willing to downplay Trump’s racism.

“It comes out right after Donald Trump is inaugurated. He references him on the album. But he didn’t do what everyone else was doing. If you remember, everybody had a Trump protest song. Everybody was talking trash,” Moore says. “He’s definitely attuned to what’s going on. He’s just not going to comment on it publicly. Or if he’s going to comment, he’s going to put it in the music in a really abstract, artistic way where it influences the conversation. If you listen to it, it’s like, ‘Is he really talking about this, or is he talking about this other thing?’”

Lamar has been mostly silent since the Black Panther soundtrack and is likely due for a new release soon. Nobody yet knows when that will be, but fans and music critics alike all assume that Lamar has several more brilliant albums in him. And his past work, as The Butterfly Effect shows, is more relevant now than ever. With the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the Black Lives Matter movement and its protests against police brutality have entered the mainstream conversation in a new way. Even large corporations are now scrambling to show public support for the cause, often clumsily attempting to paint themselves as anti-racist.

“I’m glad that it’s coming out now,” Moore says of his book. “It’s also coming out a month before this historic election. And we also have the recent news of Kamala Harris being the VP. I feel like there are a lot of things aligning that makes it seem like it’s coming out at the right time. I’m also thankful because his music is timeless.”

It’s probably not possible yet to see all the ways that Lamar has contributed to the larger dialogue. Many of the ways are subtle. But Moore makes a strong case that Lamar has helped broaden the conversation around Black identity in a way that will continue to have ripple effects.

“In current culture, there’s this rush to deem everything GOAT-worthy or amazing. I feel like more than anything, Kendrick’s impact is that he showed everybody that he’s a human,” Moore says. “He rapped about his family and friends. He rapped about struggling with self-doubt, depression. He’s talking about how he struggled with suicidal thoughts. What he did for Black America was to show the rest of America that we’re three-dimensional people. That’s even how I ended the book. Where he’s like, ‘I’m just a guy. I’m just talking about stuff that I can relate to.’”

But the truth is that Lamar has influenced his audience in a unique way, and even primed Black America and its allies for political action, as Black Lives Matter organizer Banjo attests.

“Kendrick, he does his part,” Banjo says. “He’s made his music, and he’s going to continue to make music. It’s up to us young organizers and young Black people to love what he’s saying, but then to apply the message moving forward. To really deal with these problems that require a whole restructuring of our society that works for all of us. So let’s use his music as a guidebook to become the people we want to be to make the society that we dream of.”