It’s a scene I love any time I pick up my daughters from school. I pull off Capitola Road into the Live Oak Elementary parking lot and hurry over to the gate where my first-grader and second-grader will soon come bouncing out. One by one, other parents arrive; some speak Spanish, some English. I look around and see posters, like one announcing “Dia del Niño,” that is, Day of the Child, with promises of “Almuerzo BBQ” and “musica para disfrutar.”

Great, who doesn’t like barbecue and music to enjoy? Then, finally, comes the familiar tinkling jingle of the bell announcing the end of the school day, and the kids file out, teachers alertly matching them with their parents. I hear a mix of Spanish and English—a chorus that touches the soul. The afternoon California sun is filtering down on us, a little community pulled together by a shared vision of making it a priority to try to raise children who can talk to other people, including people from different backgrounds.

DOUBLE TALK

The Live Oak Elementary dual-immersion program is part of a broad movement in California and nationally toward bilingual education as a fundamental building block for educating young people to have life skills. Teachers must receive extra training to teach in such programs, so they’re only involved if they believe in the effort. The scene at school pick-up reminds me how lucky I am that we live in a community where such a program is offered. My kids can learn from motivated, committed teachers energized by their passion for immersing students in Spanish and English.

Last week, second-grade teacher Maria Isabel LeBlanc stood near the school’s front gate after the bell sounded. She spoke in English about her love of teaching while offering friendly instructions to one student and her father in Spanish—she’s entirely bilingual. “This is my first year at Live Oak,” LeBlanc says. “There’s a good spirit here. I feel like it’s a little sunny spot here, a little happy place. The kids are so sweet to each other.”

Interestingly, that’s an oft-touted benefit of dual-immersion programs; students get along better with fewer disciplinary issues. Live Oak Elementary is three years into offering dual-immersion instruction in Spanish and English, starting students off in kindergarten with 90% Spanish and 10% English, moving on to 80-20 in first grade, 70-30 in second, and so on.

“At Live Oak Elementary, our mission is to inspire a lifelong love of learning and promote the development of bilingualism, biliteracy, academic achievement and cross-cultural competencies in all of our students,” the school’s website explains. “Not only are students immersed in the language, but they are exposed to important aspects of cultures from around the world. Through the dual immersion program, students will discover their voice in not one but two languages. Students will better understand the world around them and their unique place within it.”

So far, the program is off to a strong start, based on numerous interviews and my own observations. “It’s been amazing; it’s been phenomenal,” says Live Oak School District Superintendent Daisy Morales, who oversees Live Oak Elementary and four other schools. “We just did our two information nights. We’re almost at fifty applicants wanting to come in next year. Parents feel a lot more included.”

For both families and children, it’s empowering. “They share it as bilingualism is your superpower,” Dr. Morales says. “You’re going to learn to manage two languages in your head. Not everybody can do that.”

New signups are critical since each year, kindergarten classes are added. The new program began with two kindergarten glasses of kids, most of whom are now in second grade at Live Oak, headed for third grade next year, knowing most of the other children in the program. They’ve all been on quite a journey together. The first year was primarily conducted via Zoom because of the pandemic, an added challenge for a brand-new program. “It was definitely a learning year,” Jessica Mata, a kindergarten teacher that year, told me. “Everyone was just trying to figure it out and survive and get some learning in when it was possible.”

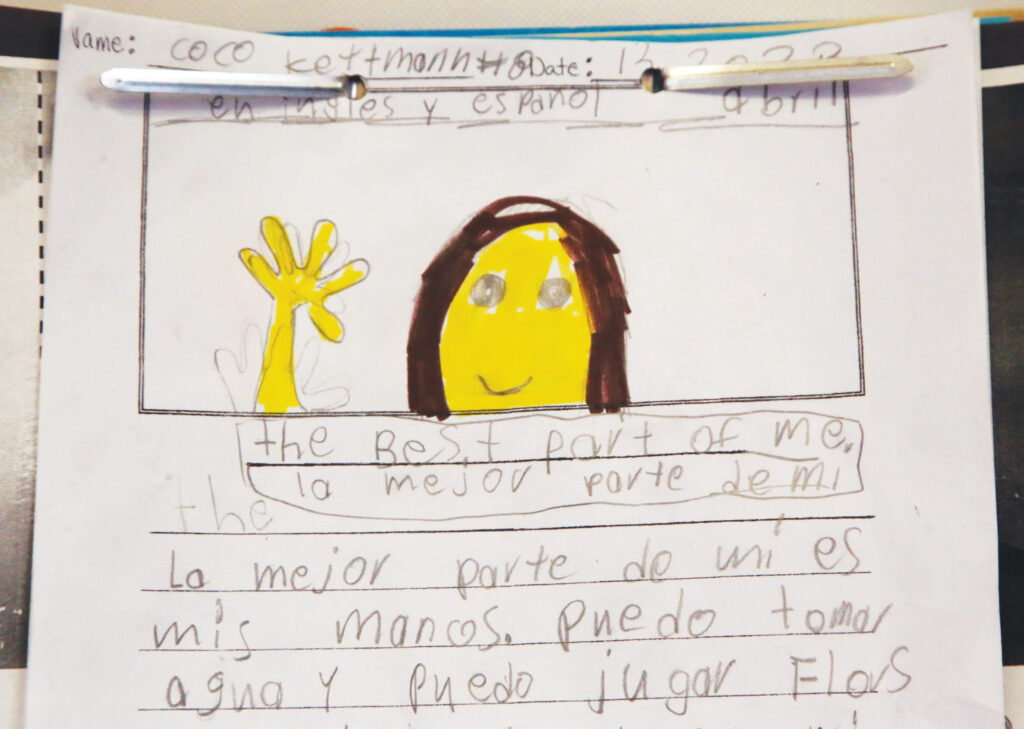

Mata has a point, as I know as a parent. Our older daughter, Coco, was one of those kids we’d have to pull in from playing outside at home to sit at a computer screen, looking at little postage-stamp-sized rectangles with a fellow kindergartner’s face in each one, trying to connect, trying to learn. It all worked better than it felt like it should have. I credit that to the fantastic dedication and talent of teachers like Mata and Karla Atencio (and, later, LeBlanc), who show some awe-inspiring ability to give of themselves and find joy in the hard, draining work of trying to be alert to the individual needs of every child.

EXPANDING HORIZONS

The United States is the outlier when it comes to language education, and it’s basically a national scandal, so far as I’m concerned, that so many school districts under-prepare their students for a 21st-century economy in which knowledge of other languages—and cultures—is often a key factor. Consider this jarring fact, as reported last year by U.S. News and World Report: “While roughly half the global population speaks at least two languages, only about 20% of U.S. residents can say the same.”

All but seven U.S. states now offer some dual-immersion elementary-school education, but the majority are in California, Texas, New York, North Carolina or Utah. More information is available at duallanguageschools.org.

I happened to be on the phone recently with Congressman Ruben Gallego of Arizona, a candidate for the United States Senate next year and a national Latino leader on the rise. Gallego’s six-year-old son is in a dual-immersion school. In another two or three cycles, I could see him as a strong candidate for Vice President or President.

“It’s not just a language, it’s part of my family’s culture, and we want to make sure that he has the ability to connect to his family and his culture always,” Gallego told me. “Even though I speak Spanish, it’s harder than you think to teach your kid Spanish. That’s why I try to reinforce it with a school that does it.”

That’s the beauty of the concept: It’s good for families that speak primarily Spanish at home, families that speak both Spanish and English or families that speak mostly English—and even for the random family that speaks, say, English and German at home (my family).

My wife and I had actually been planning to have our daughters attend the school assigned to us, Santa Cruz Gardens Elementary, and I, for one, was looking forward to—how cool is this? —walking to school on a trail high on the forested slopes of Arana Gulch, a twenty-minute stroll from where we live. Instead, Coco and her younger sister Anaïs have gone on a different sort of journey to school, toward the undiscovered country of fluency in an additional language.

The great part for us was that this was partly Coco’s choice. My wife and I heard about the Two-Way Immersion Program at DeLaveaga Elementary and mentioned it casually to Coco, then five. I thought she would forget all about it, but instead, she brought it up later—more than once.

Our girls have spoken German and English from their first words, so adding another language naturally appealed to us. I can remember early conversations with Coco pointing out the obvious fact that the more languages you speak, the more friends you might be able to make.

I know many parents worry about such programs—and their potential to slow down their children in some ways. If they are immigrant families, they often want their children to focus on English to gain every advantage in their studies—and on tests. Dr. Morales, the Superintendent, makes a compelling case that, while understandable, those concerns do not square with the data.

“Research tells us that kids can easily handle six to seven languages simultaneously,” she says. “It’s more about the parents’ concern. Will they be a little behind at first? Maybe. It takes five to seven years. Give your child those five to seven years to show they’re completely bilingual because once they hit that threshold, they outperform English-only kids every time.”

It’s a question of looking at short-term concerns, like growing pains, versus seeing a child’s education in a broader context. I care most about equipping my children to face an uncertain future, where the more people they can talk to from different countries and communities, the better their chance of continuing to develop. The U.S. is a country of immigrants, and California continues to show the cultural and economic power of embracing immigrants.

Strikingly, the rise of dual-immersion programs around the country has led to a surge in book sales, leading to “Book Publishing’s Bilingual Boom,” as Publisher’s Weekly recently reported.

“The U.S. market for Spanish-language titles is largely being driven by bilingual families, schools that offer dual-language classes and libraries that service communities with large numbers of Spanish speakers,” PW writes.

“With more than 40 million Spanish-speaking readers and language learners, according to the Census Bureau, the U.S. has the fourth-largest Spanish-speaking population in the world, after Mexico, Spain and Argentina. What’s more, if demographic trends continue, the Instituto Cervantes estimates that by 2060, 27.5% of the U.S. population will speak Spanish, which would make it the second-largest Spanish-speaking country in the world after Mexico.”

BUILDING COMMUNITY

These trends have personal resonance as well. My great-great-grandfather Gerhard Kettmann was a 49er. He left Germany in 1849, came to America, found some gold in California and settled in the San Jose area. My mother’s family comes from Mexico and Spain. My dad wanted me to take Spanish in junior high, so I took French to annoy him, and I do love French, but unfortunately, I’ve never been able to speak the language naturally.

I lived in Central America for half a year in the late 1980s and did the whole Antigua Guatemala immersion thing and can muddle around in Spanish after much flailing. I think of myself as someone with a talent for learning languages badly, always having the feeling of playing catch up. I believe actual, deep knowledge of a second language—and third and beyond—is a precious building block.

I have a lot of friends who thought they would raise their kids bilingually, but along the way, it just didn’t happen. Maria Isabel LeBlanc is an excellent example of someone whose parents insisted she learned multiple languages fluently. Her Cuban-born father and Colombian-born mother raised her, first in New Orleans, then in Texas, then in Saudi Arabia and finally in the U.K., with a firm grounding in English and Spanish.

“Being bilingual has helped me all my life,” she told me, “being able to travel all over, and professionally, and being more accepting.”

Here she calls out a quick, musical torrent of Spanish.

“The kids don’t just learn Spanish; they learn to be more accepting,” she says. “It feels like once they have it, they have it.”

LeBlanc raised her daughter, Sofía, bilingually, and guess what? “She wants to become a dual-language immersion teacher. What she noticed, visiting my class, was how everybody gets along.”

Dr. Morales and Live Oak Elementary principal Greg Stein, who lived and taught in Spain for years, emphasized that the deeper goal of dual-immersion education has to extend far beyond the classroom and beyond language acquisition to building communities. It makes sense, right? It’s one thing to learn “bailar” as a vocabulary word and another to be invited into another family’s home, with roots in Mexico, for a social occasion where people are dancing.

“We’re exploring this right now,” Stein says. “There’s the academic experience, but we also need to make it more of a cultural experience—for the kids and for the families. We’re working on that.”

Stein is a model educator. I see him smile most every day our paths cross when picking up my daughters, and I’ve watched him handle the occasional tricky situation with aplomb. He loves what he’s doing. He’s on a mission to encourage everyone at the school to treat each other with respect and dignity, whatever job they hold, and to show the power of bilingual education.

“I’ve been in bilingual education for years, and it’s a miracle how kids just pick up languages,” Stein says. “It’s unbelievable. I think it opens the door to relationships. Being able to speak the language at a level these kids will probably be able to speak, opens the door to deep relationships—both to people and to cultures. That’s a catalyst for empathy.”

I’ve been thinking about bilingual education and its more profound value since at least the 1980s. My sister Janette Kettmann Klingner was a public school teacher in San Jose and Santa Cruz. She then returned to school to earn her Ph.D. and became a nationally recognized expert on Spanish-language education. She emphasized in her work how education works best when family members—and communities—are engaged.

“There are many misconceptions about the involvement of parents and families of English language learners in their children’s education,” she wrote, with co-authors Alfredo J. Artiles and Kathleen King, in a chapter on Bilingual Special Education in the 2008 Encyclopedia of Bilingual Education.

“However, research from the National Center for Education Statistics in 1995 shows similar patterns for minority and nonminority parents’ involvement in their eighth-grade students’ education. Educators must be aware of and challenge the biases that shape the interpretation of different levels and types of parental and family involvement in their children’s education. A useful principle is to consider that different communities and families have different norms about family involvement in the school setting.”

Another helpful principle is to acknowledge that norms change, they shift over time, and the power of dual-immersion education is its potential to bring communities more into contact with one another. Parents, teachers and administrators go out of their way to hold different events to unite people—and more is on the way.

“Our English-speaking parents want to connect with our Spanish-speaking parents,” Dr. Morales says. “So next year, we’re looking at doing something formally or informally, where they can meet up and have buddy dates.

We’ve been talking about: “How do we make this happen? How do we provide those spaces for the parents to come together?” We’re trying to build it so it feels more like a community, so the classrooms don’t get so much divided into Spanish speakers and English speakers. We want to see how we can provide a basis to bring the community together and be truly a bilingual community.”