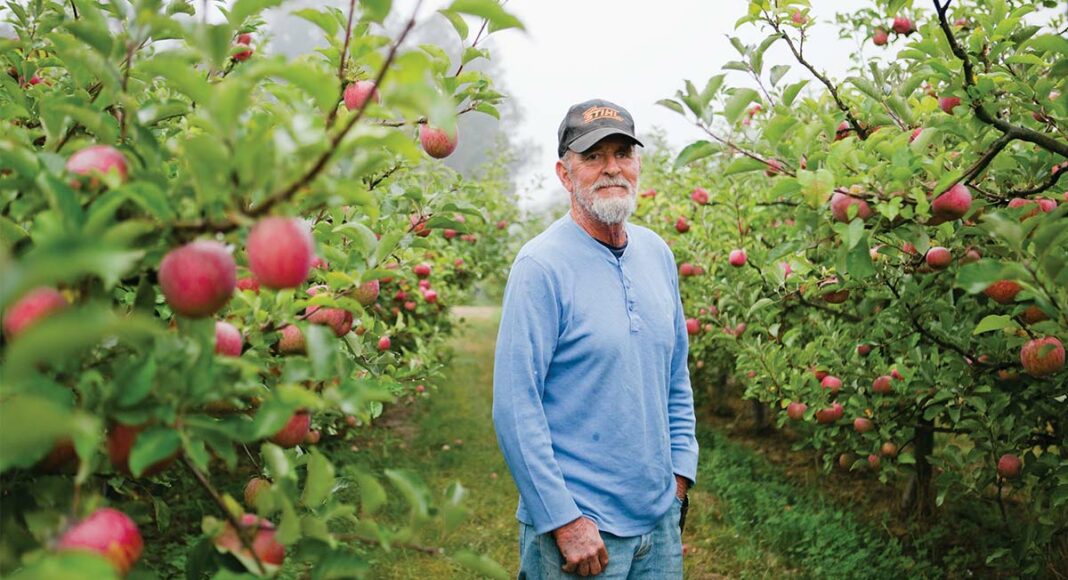

Bill Piexoto got a little excited this past spring when he started spotting flowers budding on his apple trees.

After a stretch of warm, sunny weeks, the little flowers have given way to plump fruits almost ready to be picked. “This is pretty close to a normal year. It’s really early this year, maybe the earliest ever. Everything’s happening really fast,” says the 65-year-old Piexoto.

A “normal year” is just about the best anyone could have hoped for after a 2015 harvest that Piexoto says was the worst he’s seen in his 30 years of local apple farming—one in which his harvest was down 50 percent compared to previous years. Newly appointed Agricultural Commissioner Juan Hidalgo says it was the worst apple year he’s seen in his 11 years with the county ag department.

The county’s crop report, released last month, found that apple production fell by nearly 50 percent from the previous year, as GT reported last week, even as production of most berries—excepting the delicate olallieberry fruit—blossomed. And even though local apples climbed in value per pound, farmers’ overall sales still dropped 42 percent, thanks mostly to strange weather patterns.

“It was bad pretty much across the board,” Piexoto says. “Some varieties did worse than others.”

By just about any metric, it was the worst apple year in at least three decades. The county has crop reports on its website going back to the 1980s. And the dollar amount that apple growers raked in this year—$6.3 million—was the lowest amount on record for the county, even without adjusting for inflation.

To be fair, apples aren’t quite the cash crop they once were. Acres of apple orchards, which once filled the county, are down 61 percent compared to what they were in 1987, and that land has given way to more profitable berry farms.

This year’s fruit yield was historically low, too, compared to the county’s reports, as far back as they go. Growers harvested 9.4 tons of apples per acre. That was also more than 50 percent lower than the previous year, as well as the lowest on record. The last time that number dipped below 12 tons per acre was 21 years ago.

On top of that, there’s a growing fear among some farmers that the very bad years, which used to be anomalies, could turn into the new norm as weather patterns shift, and that such changes will make an already tough job even harder.

Hidalgo and probably every apple grower in the county seem to agree on the biggest culprit for the lousy harvest: 2015’s warm winter.

In order to thrive, apples need a few hundred “chilling hours” each winter—experts have found—when temperatures fall between 32 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit and when the plant goes dormant. Last year was unseasonably warm. After a scorching winter tricked many trees into blossoming early, their crops failed. Low cumulative rainfall over the years, starting in 2012, certainly didn’t do farmers any favors, either.

“A lot of people will ask, ‘Has the drought hurt the apple, or will the weather affect farming?’” says Rich Everett, who owns Everett Family Farm and Soquel Cider with his wife Laura Everett. “This past winter absolutely helped this year. The ground’s been pretty darn dry, and the aquifer’s pretty empty. How many more years can we go like this? I don’t know, but we’ll keep our fingers crossed for another wet winter.”

South County’s rich history of apple growing goes back more than 100 years and can still be seen in some businesses, like Watsonville’s Appleton Grill, whose name has served as a nod to local history since it opened three years ago.

Martinelli’s, probably the world’s most-loved soft apple cider maker, is still headquartered in Watsonville. Even in the face of change, the company has committed itself to the local apple industry. Martinelli’s has been working with growers to rejuvenate local orchards—preserving established ones, as well as encouraging people to plant new ones.

While last year’s tough apple season hit all growers, not everyone suffered the same losses. As anyone who’s driven the length of our relatively small county knows, the weather can change quickly from one area to another. Those microclimates can create some noticeable differences, says Chris Mora of Melody Ranch, which seemed to fare a little better than some orchards.

“If you get really windy days, it could affect you because it could blow blossoms off the tree,” says Mora, seeking refuge from a hot sunny day at the downtown farmers market under the shade of a tent. His family’s orchard, tucked away on Green Valley Road, is sometimes spared, he says, from heavy gusts and more intense weather patterns. “Different areas have different [climatic] effects.”

This year at least, the harvest looks strong, across the board, and it’s coming in earlier, too.

Nicole Todd, co-owner of Santa Cruz Cider Company, says she and her sister Natalie Henze suddenly have more apples than they know what to do with—a welcome change after getting just one eighth of their normal harvest in 2015 at a Corralitos orchard they help manage.

There are many factors playing into any given harvest, and farmers don’t know exactly how the year will take shape. But this past winter’s cold, rainy months amounted to a season most locals would have called “average” 10 years ago, and that’s a good thing for growers. A stretch of warm sunny days in the late spring helped as well. Everett says the fog that rolled through in August seems to have slowed the ripening process, hopefully making for a better crop. Farmers have already started picking their Gravenstein apples. In a couple weeks, Everett says, his workers will start picking Galas and Honeycrisps—followed by pippins, which are about four weeks away.

Bad years aside, most of the county’s shift away from apples in recent decades has nothing to do with weather and everything to do with dollars.

And though it could be tempting to lament the decline of a food that at one time symbolized South County, Everett says the market will always dictate what the farmers will grow because farming is a business. As berries have grown more profitable, more farmers have switched over. Berry growers pulled in a whopping $404 million in 2015 on 6,700 acres.

Farming, as a line of work, requires growers to keep a finger on the pulse of what customers want. Perhaps Brussels sprouts will be the next big thing, as sales jumped 30 percent this year, driven mainly by an increase in their value. It’s a change that Hidalgo attributes to a growing buzz about Brussels sprouts and cooking shows talking about more ways to prepare them.

Generally speaking, crops come and go, says Piexoto, who adds that he remembers when there were only 50 or 100 acres of berry land in the county.

“It’s a cycle. If you look at the history of apples in Watsonville, apples were huge at one time,” says Piexoto, who has a 14-acre property, most of it orchards for apples, along with a eucalyptus grove and a reservoir—plus a few houses, sheds, barns. “Things have changed over the years. Flowers were huge here for a while. And apples were huge, and head lettuce was huge, and right now berries are huge. You never know, but you gotta think someday something’s going to replace the berries. They used to grow hops around here. They don’t grow many hops here anymore.”

Still, Piexoto has no plans to switch out of apples, and neither does Everett, as apples are what they know and enjoy. Anyway, Everett says, tearing up trees and planting a different crop has a steep learning curve that requires, for instance, monumental investments in buying new equipment and finding or training a new crew.

“We’re always thinking about the long-term. We’re thinking about the future. When you plant an orchard, it’s generational,” he says. “Our trees are going to last 100 years, so it’s not only for us. It’s for the next generation.”