In the late 1970s, a small group of African-American community leaders and activists began pushing for the renaming of the Laurel Community Center, at the corner of Laurel and Center streets, in honor of the slave—mistakenly referred to as “Louden” Nelson—whose enduring legacy in Santa Cruz County history dates back to before the Civil War.

His life story, as was then known, was a small, torn, and incomplete patchwork of legend and folklore that had never been fully flushed out in the decades since he died. What had been etched into the collective history of the region was that, at the time of his death, in 1860, Nelson had “left his entire fortune … to Santa Cruz School District No.1.”

The effort to honor Nelson was widespread. In 1977, State Sen. Henry Mello, the late bulldog legislator from Watsonville, ushered through a resolution in Sacramento that paid tribute to Nelson’s “magnanimous spirit [that] rejected any bitterness or envy because he had been denied education, but on the contrary, caused him to treasure it all the more ….”

There was also a proposal for a monument at the downtown post office, located on the plot of floodplain along the San Lorenzo River where Nelson once farmed and worked as a cobbler. The focus of that effort soon shifted to the headquarters of the Santa Cruz City Schools, on the Mission Hill property that was purchased by Nelson’s bequest and where “Louden Nelson Plaza” was dedicated with a 1,300-pound granite monument declaring that Nelson had “left his estate to Santa Cruz schools [because] he believed in education for all people.”

Much of the energy around the effort to honor Nelson in the 1970s was initiated by Lowell Hunter Sr., a minister with the Santa Cruz Missionary Baptist Church, who as a candidate for Santa Cruz City Council had criticized the city for its failure to have any African Americans in a single administrative position or on the police force. Hunter founded the “Louden Nelson Association” and served as its president, urging local political bodies to find some place — anywhere—to memorialize Nelson’s legacy. He once again shifted his focus to Mission Hill Junior High, but could not generate support sufficient to usher in such a name change.

Finally, with Wilma Campbell and Helen Weston joining his efforts, along with many others in the local African American community, Hunter took aim at the recently opened Laurel Community Center, located at what was formerly Laurel School, then operated by a joint agreement between the city of Santa Cruz and the county. The movement garnered unanimous support from the city’s Arts Commission, and the County Board of Supervisors said they would support whatever the Santa Cruz City Council decided, and on Tuesday, Oct. 23, 1979, the council voted 6-1 to rename it the Louden Nelson Community Center in honor of the elusive figure who had died more than a century earlier.

There was, however, one slight wrinkle amid all the hoopla: Louden Nelson was not his real name.

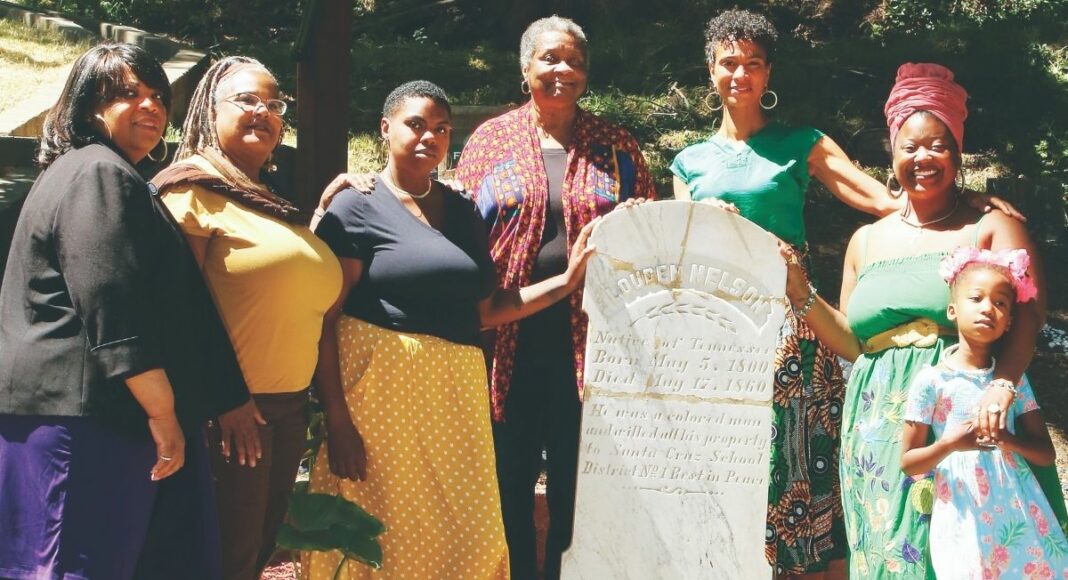

A simple, honest, albeit somewhat careless mistake in recording Nelson’s name in the 1870s had been compounded for more than a century. As early as the moment when Nelson’s probate notice appeared in the pages of a local newspaper in June 1860, he had been identified as London Nelson. Within months, however, his name began to appear as “Louden” Nelson in various publications (and several variations thereof), so that when a tombstone was placed at his grave in Evergreen Cemetery, his epitaph, carved in white granite with gold-leaf lettering, read as follows:

Louden Nelson

Native of Tennessee

Born May 5, 1800

Died May 17, 1860

He was a colored man

and willed all his property

to Santa Cruz School

District No. 1. Rest in Peace.

The name—and the broad outline of his legacy—had literally been set in stone.

That said, anyone who consulted the local historical archive at the time was well aware that there was controversy over Nelson’s name. One of the best local historians in the early 20th century, Leon Rowland—who wrote a regular history column for the Santa Cruz Sentinel and authored a history book titled Annals of Santa Cruz (1947)—consistently referred to him as “London.” Rowland had no equivocation. Margaret Koch, who penned local history in the 1950s through the 1980s, while initially using “London,” had acknowledged that “his name might have been ‘Louden’ instead of ‘London,’” though she never attempted to set the record straight.

That task was left to the late Phil Reader, a dear friend and colleague of mine, who in 1984 broke the code. Using recently accessible slave records and genealogical materials compiled by the Mormon Church in Utah, Reader was able to trace Nelson’s birth to a North Carolina cotton plantation owned by a slave master named William Nelson. As was the practice of the time, slaves were forced to assume the family name of their owner. William Nelson, as Reader discovered, in turn, named the slave children born onto his plantation after English place names: Canterbury, Marlborough, Cambridge—and London.

Reader’s breakthrough research raised a huge commotion as he and others in the local history community led an effort to force a name change. To cut a long story short, that effort failed, as many in the local Black community who had fought for the initial naming of the community center had become attached to the name. Moreover, the funds required to change the name, they argued, could be better spent somewhere else. The broader community had also become used to it. They didn’t want to endure any blowback.

The name stayed. London Nelson’s true name and story faded into the background.

Members of the ‘Louden Nelson Memorial Committee’ from February 1953 at Nelson’s grave in Evergreen Cemetery. Left to right: C.H. Brown, chairman of the memorial committee; Frank Guliford, president of the Santa Cruz Improvement Club; Rev. Dennis E. Franklin, NAACP; Rev. W. M. Brent, pastor, Santa Cruz Missionary Baptist Church; Herman Gowder, secretary, Memorial Committee; and Henry Pratt, president, F. & A. club. The group paid honor to Nelson during “National Negro History Week.” PHOTO: COVELLO & COVELLO

Historical consciousness and reverence for history, more often than not, reflect the values and social dynamics of the era from which they spring. Last July, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s brutal and public murder at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement worldwide had a profound impact on longtime local resident Brittnii Potter, who had been raised in Santa Cruz and had graduated from Santa Cruz High School in 2007.

Potter had a direct link to the Nelson story. Her grandmother had been a member of the Black community that had originally pressed for a name change at the Laurel Community Center in the 1970s. When she was in elementary school, Potter recalled walking with her mother as they passed the community center. She told her daughter that the center had been named for one of the first Black men to arrive in Santa Cruz, but that the man’s name was “actually London and not Louden.”

“I remember feeling a mix of emotions [at that time],” Potter recalls. “Feeling proud that this community center that I had grown up going to was named after a person who looked like me, Black, but also feeling an overwhelming amount of anger that the city that I called home didn’t care enough about a person who looked like me, and the misnaming of the community center made me feel like it was painstakingly true.”

Potter, a mother of two whose family runs the popular Persephone restaurant in Aptos, says that “2020 was a year of momentum in righting some wrongs of the past.” She felt compelled to do something in Santa Cruz. “The center was the first thing that came to mind as something that I could do within my own community and reclaim history that had long been forgotten, and I immediately thought of London Nelson. I felt the time was right to get this accomplished, so I set out on this journey.”

Placing a petition on change.org calling for the renaming of the center, Potter secured over 1,000 signatures. “What better time than now not only to rename, but reclaim history!” Potter declared in her petition. “As a Black woman, and Santa Cruz local, I think it is beyond imperative that we have history that is accurately named after some of our first Black leaders.”

Potter brought together a project committee that included community center supervisor Iseth Rae, Recreation Superintendent Rachel Kaufman, Civic Auditorium Supervisor Jessica Bond, NAACP President Brenda Griffin, City Councilmember Justin Cummings, Santa Cruz Equity Project founder Luna HighJohn Bey, and Sentinel history columnist Ross Gibson.

Perhaps most importantly of all, they tracked down members of the Black community who had originally supported the name of Louden. There were no holdouts left. It was finally time to get the name right. On Tuesday, June 8, the Santa Cruz City Council voted unanimously in favor of changing the name.

In addition to the name change, there were two additional caveats to the council’s vote last week: The resolution also called for the city “to pursue a more accurate depiction of the history of Mr. Nelson and [to] explore further education efforts on his contributions to Santa Cruz.”

These latter efforts are of critical import to Luna HighJohn Bey, who in addition to serving on the project committee, describes herself as a Hoodoo spiritualist. And while Brittnii Potter’s efforts were motivated by a local connection to the story, Bey’s attachment to the issue emanated from across the continent to her Anacostia neighborhood in Washington, D.C., the home of the legendary abolitionist Frederick Douglass and a cultural center for D.C.’s African American community.

“As the granddaughter of the First Black Woman Park Ranger,” Bey noted, “exploring county and state parks, reading placards and visiting local monuments is second nature to me. I grew up going to the Fredrick Douglass home as an after-school hangout with my cousins. So when someone told me that ‘Louden Nelson’ was a Black man and had a center named after him, my curiosity led me directly to the research of local historians.”

After arriving in California a little more than a decade ago, Bey eventually found her way to Santa Cruz. She immediately began to pull off the veneer of the community and dig into its historical underbelly. “I am invested in honoring the legacy of those who come before me everywhere I go,” she declared. “And in my experience, when you look at the beginnings of so many great cities, specifically European Colonial settlements, there is a Black person who was integral to its legacy.” It was an act of “synchronicity,” she says, that brought her together with the committee seeking to coordinate the name change.

Part of her goal is to reframe, broaden and contextualize Nelson’s life. “The narratives we have about the past are often based on the interpretation of historical data,” she says. “This means that the narratives that are constructed pass through the researchers’ lived experiences and biases. This leaves space for nuances, patterns, cultural practices that may not be seen or considered due to a lack of this lens. This is why it is important for this data to be reengaged with the tools and technology we have access to now, and by researchers with the intimate knowledge of the Crimes of Slavery.”

Much of what has previously been written about Nelson (including my own work, quite frankly) has been done so through the prism of white privilege. None of it has stretched to include the horrors and moral criminality of chattel slavery. Assumptions and depictions of London’s life before arriving in Santa Cruz were rendered without that “intimate knowledge” referenced by Bey.

“We cannot assume,” Bey adds, “that London Nelson came to California willingly. He was being trafficked to do labor. He was taken away from everyone he knew and loved. The nature of the crimes of slavery means it is more likely than not that Mr. Nelson had children, had a spouse he loved. That the person who was trafficked with him, Marlborough Nelson, is more than just the property of their Trafficker, but was someone of kin to London Nelson. For Enslaved people, blood relation is not what keeps us together, nor does that define kinship. A shared ‘last name’ does not tell us about who they are to each other. This is a history that deserves to be re-explored.”

Bey’s perspective sheds new light on what we think we know about London Nelson’s life.

William Nelson’s youngest son, Matthew, eventually “inherited” London from his father, and in 1849, the discovery of gold in California lured him westward. Promising both London and Marlborough their freedom if they joined him, Matthew Nelson set up a claim on the American River, where the trio was to mine successfully for four years.

Although California was a so-called “free state” when the Nelson entourage arrived, neither London nor Marlborough would have been free men upon their arrival. A fugitive slave law had been passed in Sacramento in 1852. Did London receive a percentage of William Nelson’s earnings when they parted ways? Did Marlborough?

With his freedom eventually secured, London Nelson eventually found his way to Santa Cruz in 1856. Santa Cruz was an abolitionist stronghold in its pre-Civil War era, and thus provided a tolerant, if not necessarily egalitarian, setting for a freed slave of African descent. Black residents held no rights here; they couldn’t vote; they could not testify in courts of law.

By then, presumed to be in his mid-fifties and suffering from poor health, Nelson raised small crops of onions, potatoes and melons and worked as a cobbler to support himself. He joined the local Methodist Church and, in early 1860, he bought a rough-hewn cabin and a small parcel of land on what was then known as the San Jose Road (now Water Street), behind the present-day downtown post office. From there, according to legend, he was able to view children playing on the grounds of the Mission Hill school.

His health, however, continued to deteriorate. He began to cough up blood, and in April 1860 a local physician, Dr. Asa Rawson, realized Nelson had only a short time to live. Rawson and Elihu Anthony, a friend of Nelson’s from the Methodist Church, recorded his last will and testament, in which Nelson bequeathed “unto Santa Cruz School District, No. One, all of my estate … forever, for the purpose of promoting the interest of education therein ….” He signed the document with an “X.”

Nelson died a short time later, on May 17, 1860. His property, onion crop, a note due to him from Hugo Hihn, and assorted other belongings were valued at $377. The following day, the Santa Cruz Sentinel, identifying him solely as “Nelson,” paid substantial tribute to the “pioneer Negro” whose soul “beat responsive to noble and benevolent emotions.” The Santa Cruz News, in an obituary titled “Old Man Nelson,” lauded him as “a man respected by those who knew him well enough to appreciate his good sense, his honesty and fidelity to friends.” Neither article made reference to his first name.

While the details of Nelson’s life are piecemeal at best, his legacy, as rendered by the exclusively white media over the decades that followed, endured a circuitous journey.

In 1868, during Reconstruction, a Sentinel editorial pointed out that while “Nelson” had bequeathed his property to the local schools, “There are a half-dozen colored children in the District who … are anxious to be educated. Yet the white Christians deny them this boon, and refuse them admission.”

Three decades later, while the U.S. was colonizing land in the Philippines and Cuba, a blatantly racist article in the Santa Cruz Surf of 1896 was headlined “N****r Nelson…The Story of an Every Day Darkey Who Turned His ‘Watermillions’ Into Dollars for the White Pickaninnies.” In that article, Nelson was referred to as London, although only a few weeks earlier he was identified by the same paper as “Ludlow Wilson.”

That same racist article, however, noted the shameful irony of his plight. “He had been born and brought up in slavery,” the paper observed, “but he was too full of love of freedom to wear the shackles always, and so he worked and struggled until he was able to buy himself—to buy his own flesh and blood, his own body and brains, and the right to do with them as he would.”

Nelson received scattered coverage over the next few decades. Through the modern miracle of digitized newspapers, however, I recently discovered something I had not realized before: that in the 1930s, Nelson’s legacy had garnered national attention. In June 1934, on the front page of the Oakland Tribune, in a popular column called “The Knave,” Nelson’s legacy received a full-throated recognition when it was noted that students from Mission Hill School “marched to the Evergreen Cemetery where they decorated the grave of London Nelson, Negro, ex-slave and one-time shoe-maker.”

From Nelson’s cabin, noted the Knave, “he could see the two room wooden school house where sessions had been suspended because of lack of funds.”

Two years later, in 1936, the Sentinel published a similar story, albeit using the name of Louden. The story went viral over the newswires. It appeared in newspapers across the country, from coast to coast—from Utah to Pennsylvania, from Texas to New York. As late as March 1937, it appeared in Kenosha, Wisconsin. The headlines read: “Ex-Slave Aided School,” while the story mistakenly implied that his tombstone had only just been erected. What was being treated as a news story had happened in the previous century.

The details be damned, London Nelson’s story had gone national—and even crossed over into Canada.

It is only fitting that the formal ceremonies commemorating the name change of the city’s community center in honor of London Nelson should be held there this coming Saturday, at the annual Juneteenth celebration, where it has taken place for the past 30 years—ever since Raymond Evans, then serving as assistant director of the center, decided it was time to bring the Juneteenth celebration to his adopted city.

A native of Texas, Evans once told me that he was shocked to find that there were no traces of Juneteenth in the region when he first arrived here. He had grown up in the predominantly all-Black neighborhoods of Dallas, and from his earliest memories, Juneteenth was celebrated by the entire community. It was, he declared, “Black America’s Fourth of July.”

In recent years, the role of coordinating the Juneteenth celebration has been taken up by Ana Elizabeth and her brother, music maven David Claytor of Sure Thing Productions. “I love acknowledging the significance of Juneteenth,” says Elizabeth, “but more I love the Black Santa Cruz family coming together yearly. It’s a moment of appreciation that we are still here as one of the smallest groups in this county. It’s one of the few times we come together to love each other up as we are able to look upon a sea of faces that look like us, restoring us to keep on with our work for equity and justice in this community.”

One thing is for certain: the spirit of London Nelson will pervade the festivities. He’s going to feel right at home.

The annual Santa Cruz Juneteenth celebration will be held Saturday, June 19, at Laurel Park and the London Nelson Community Center, from 1-4pm. Live music, soul food, and dance will be featured. A basketball clinic begins at 2pm at 440 Washington Street. The event is free.