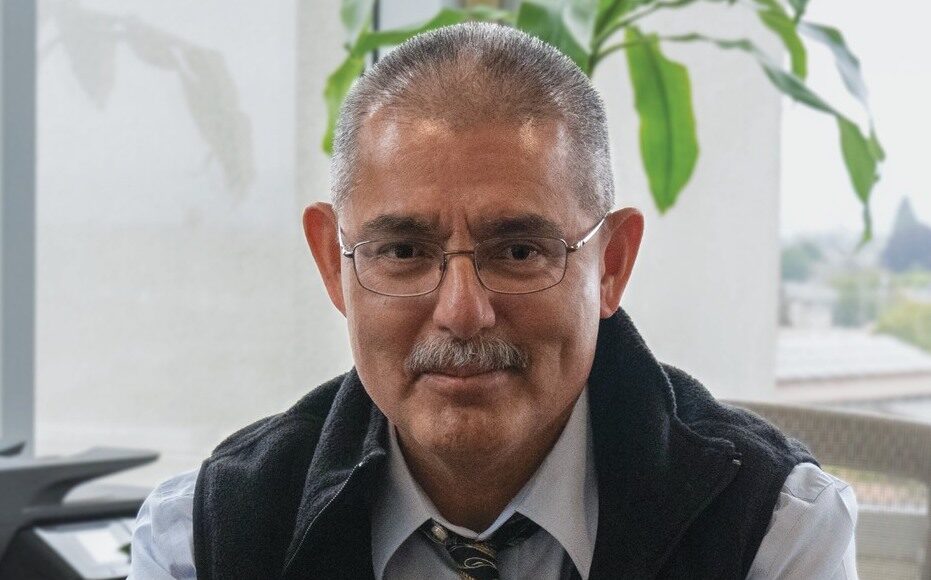

New Watsonville City Manager Rene Mendez stepped into the leadership role on July 1.

Just three days later he was driving Watsonville City Councilman Jimmy Dutra through the Spirit of Watsonville Fourth of July Parade in a Chevrolet Corvette, and, in the time before and after, working feverishly with staff on a key ballot measure for the November election, and meeting with several local organizations.

“It’s a balancing act,” he says.

Mendez, 57, was named the city’s chief executive in April, bringing to an end a months-long search to find a replacement for former city manager Matt Huffaker, who is now the city manager at Santa Cruz.

He brings in three decades of experience in state, county and city government, including the previous 18 years as the city manager with the City of Gonzales. In that role, Mendez, among other things, led efforts to create a Health in All Policies initiative, a youth council that represents the city’s young people at city council and school board meetings and an ambitious microgrid energy project. He was also instrumental in convincing agricultural industry giants Taylor Farms and Mann Packing to set up in the Monterey County city of roughly 9,000 residents.

Mendez says he sees several parallels between his new job and old stomping grounds, but explained that he first wants to embed himself within the Watsonville community before moving forward with any initiatives.

“I’m going to be available and accessible, and I want to learn,” Mendez says. “I have my thoughts, ideas and approaches, but part of the art of this is to figure out how it works … Clearly, there’s a lot of great stuff going on, and, to me, it’s how I can support and enhance that and not get in the way of the stuff that’s going on.”

But, he adds, there are three issues that will likely be focal points of his tenure with Watsonville: housing, economic vitality and community engagement. All three issues, he explains, are interconnected, and have big implications for the city’s large population of youth and young adults. He says the city should help in any way it can in creating paths for its younger residents to access higher education, find a good-paying job and, ultimately, own a home.

“How do we tap into [this generation] to get more involved in their community?” Mendez says. “Obviously, we want to work with all segments of the community, but one of the challenges and goals that I see is how do we bring in segments of the community that have not felt that they’ve had access or participated. It’s not easy, and it’s not going to happen overnight. But that doesn’t mean we’re not going to keep knocking on the door.”

Mendez signed a five-year deal with a base annual salary of $240,000.

He takes over during a time in which Watsonville’s leadership and direction could see big changes. Three city council seats will be up for grabs in the upcoming Nov. 8 election, and Watsonville voters will also decide whether to support the extension of current outward growth restrictions and a half-cent sales tax measure.

He says he made the decision to leave Gonzales for Watsonville—a move made easier after the recent graduation of his two sons from Gonzales High School—to continue his “professional growth.”

“One of the things that I hope people find out about me is that I don’t sit still—I’m not a maintainer,” he says. “I think you have to maintain things but I’m always working to improve.”

Mendez is a first-generation Mexican American who grew up in the Central Valley and worked in the agricultural fields as a youth. He holds a master’s degree in public policy from Duke University. He first worked as a state legislative analyst before being hired as an analyst for Solano County and then as the County Administrator for Inyo County. He then joined Gonzales as the city’s lead public official.

It took all of two weeks for him to realize that being a city manager is “the best job in the world.”

He came to that realization when a woman randomly walked through his door and asked if the city had a youth soccer league. At the time, Gonzales did not. So he told her to gather the coaches and kids and the city would find the fields and equipment. That was the start of a strong partnership between the youth soccer league and the city that has paid dividends for the community multiple times.

“That was a reminder that sometimes the investment is only like 2 cents and the return is amazing,” Mendez says. “You had parents, kids, families there—salen todos. So, now, from a city perspective, you can participate, you can ask questions, you can put a table out there for information—aver que—you don’t have to force it on people because they’re already there. If the city wants to do that by themselves that would take more effort and resources … That, to me, is why I think this work is so exciting. Making those connections.”