Last summer, Hulk Hogan sat in a Florida courtroom, wearing a black bandanna of mourning, chewing on his biker mustache as he tried to rehabilitate his reputation in court.

The trouble began in 2012, when the celebrity gossip website Gawker published a cuck-video of Hogan having sex with his BFF’s wife, Ms. Heather Clem. The BFF—Todd Clem, a.k.a. shock-radio personality Bubba The Love Sponge—covertly ran the camera.

When the famous lawsuit’s smoke cleared, Gawker and its subsidiaries were left to face the bad end of a remarkably generous judgment of $140.1 million aggregate. The website and its subsidiaries went bankrupt almost immediately, and Univision scooped up the remaining assets for $135 million.

It seems strangely coincidental that the downfall of everyone’s favorite (and, at times, most hated) online tabloid coincided with the rise of a different tangerine-colored figment of 1980s wrestling, Donald Trump. Beyond journalists, few seemed to realize Gawker’s death was a harbinger of a greater war against the media, financed by wealthy individuals.

It was later discovered that Hogan had a secret partner funding his lawsuit. The money paid for the sordid case was, in fact, payback against Gawker by Hulk Hogan’s secret donor Peter Thiel, the prominent Silicon Valley tech financier who the website had outed as gay. Thiel now serves as an adviser to the president, who continues to call the media an enemy of the state.

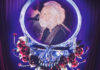

The trial is the focus of a new Netflix documentary, Nobody Speak: Trials of the Free Press, and it’s bizarre how little talk went on in Silicon Valley about a titan of tech’s actions in putting a media outlet to death.

Brian Knappenberger, director of Nobody Speak, says he encountered trouble conveying the importance of what happened in court. He’s met people who thought it couldn’t have happened to a nicer website, and that Gawker had it coming.

“I don’t think they understand that this kind of lawsuit can be used against any outlet, even in a country that prides itself on freedom of expression,” Knappenberger says. “We’re living in a time when the rich are so much richer than they’ve ever been, and because of the vanishing of classified ad revenue, journalism is more vulnerable than ever.”

Hogan’s point during the Florida trial was that the leaked tape hurt him as a man. Hulk Hogan was simply a character, created by one Terry Gene Bollea. His lawyers argued that when Hulk later went on Howard Stern to joke about the tape—to boast of both his marital and his martial prowess—that he was doing so in character. The real Bollea was not actually rocking a 10-inch schwanzstucker, as he had told Stern on the air. Instead, he was a quiet and humble guy. Bollea, not “the larger than life, All-American professional wrestler” as Hogan testified, ached for very expensive closure.

When Hogan’s lawyers, in a calculated move, dropped the “infliction of emotional distress” claim, Gawker Media’s insurer was no longer on the hook for damages. The protracted legal battle between Hogan and Gawker lasted several years, but it was only in May 2016 that first Forbes, and then the New York Times revealed Thiel, an early investor in Facebook and a founder of PayPal, had been paying for the wrestler’s expensive litigators.

Owen Thomas, the then-editor of Gawker’s tech blog, had outed Thiel as gay. Thomas, gay himself, concluded the exposure with, “More power to him.”

One could argue that this outing was a way of embarrassing Thiel. One could also point out that in a culture where the bro-ethos rules supreme, identifying Thiel as gay was a way of reminding the lords of the valley that gay people are everywhere. One could compare and contrast the way the first openly gay Fortune 500 CEO, Tim Cook of Apple, handled a similar situation: After being accidentally outed by CNBC, Cook publicly discussed his sexual orientation in an editorial in 2014.

Gawker had a self-declared mandate to publish stories other outlets were scared to touch—for reasons of what’s left of good taste in our society, of lack of the usual vetting, or of just plain ridiculousness.

The site did, however, do useful and funny work: Caity Weaver documenting the Paula Deen damage-control cruise, Tom Scocca’s essay bringing light to rape allegations against Bill Cosby, and a series of stories on leaked Sony documents that revealed in-house racism at the studio.

Thiel has contradicted himself over the years. He’s donated to the nonprofit Freedom of the Press Foundation, which has since denounced Thiel’s big-payback donation to Hogan’s lawyers. The foundation’s spokesman, Trevor Timm wrote, “Do you think that because Gawker’s demise is something you agree with that the same thing won’t happen to newspapers you like in the future?”

Personally, director Knappenberger says he wouldn’t have run the column outing Thiel if he’d been Gawker’s editor. “That doesn’t mean anything, though,” he says. “The legal boundaries aren’t crossed when that happens.”

Knappenberger says numerous examples of what’s chronicled in Nobody Speak have occurred since his film debuted at Sundance.

“John Oliver and Time Warner got sued by John Murray, a coal billionaire,” Knappenberger says. “Then there’s Sarah Palin’s New York Times suit, alleging that she’d been defamed by connection to the Gabby Giffords shooting.”

It’s been a good strategy for political billionaires to tie up periodicals in court and bleed them with the cost of lawyers, in hopes that their secrets will stay that way.

So what should journalists be doing?

“They should be rethinking libel insurance and they should be looking into ways of protecting themselves,” Knappenberger says. “In the meantime, they might want to end the practice of writing softball stories with the powerful in exchange for access. A rethinking of that kind of approach could help, and it proves it’s a good idea for journalists to ignore useless press conferences.”