For more than 14,000 years, humans have had a close relationship with wild salmon. Along the Pacific Coast, natives harvested thousands of adult salmon each fall from their spawning grounds in local rivers and streams, a catch that fed their families throughout the year.

While many cultures in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska are still deeply wedded to the salmon resource, California’s grasp has grown increasingly slippery, with only a small percentage of its historical natural breeding population remaining.

Salmon’s legacy for Californians goes far beyond its estimated $1.4 billion fishery, or its classification as one of the most nutritious foods in the world: the fish also provide a vital transfer of nutrients and energy from the ocean back to the freshwater ecosystems where they were born.

“People have done studies to show that you can identify ocean-derived nutrients from salmon in many dozens of different species, like kingfishers or water ouzels, fish-eating ducks, foxes, raccoons, coyotes—all the way up to the big predators that used to live here but are gone, like grizzly bears,” says Nate Mantua, a research scientist for NOAA’s Southwest Fishery Science Center in Santa Cruz.

Accumulating 95 percent of their biomass at sea, adult Pacific salmon die after they spawn, and their nutrient-rich carcasses, gametes (mature eggs and sperm) and metabolical waste return to the land. “It’s fascinating that, over the eons, a lot of fertilizer was provided by these dead salmon, so a lot of the wine grapes and a lot of the agriculture inland by the rivers was fertilized by salmon for a long time,” says Randy Repass of the Golden Gate Salmon Association (GGSA), a coalition of salmon advocates based in Petaluma.

Salmon’s yearly return props up an entire food web, replenishing bacteria and algae, bugs and small fish, and fueling plant growth with deposits of nitrogen and phosphorus.

“They fertilized forests as well, there are lots of studies that find salmon’s ocean-derived nutrients in trees that grow along productive salmon watersheds,” says Mantua. “And where we’ve depleted the natural runs of salmon, we’ve really degraded that connection.”

Damming a Species

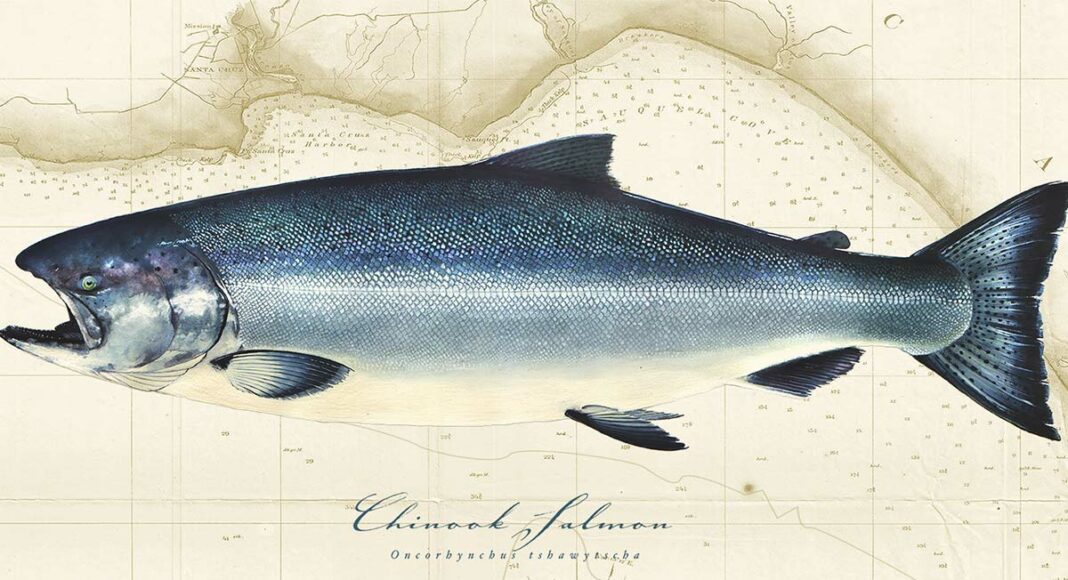

The largest salmon known to man—with adults often exceeding 40 pounds, and capable of growing to 120 pounds—the chinook (aka king) salmon is the pride and joy of California’s salmon fishery. Not so long ago, the Central Valley watershed was one of the biggest producers of naturally breeding chinook salmon in the world, second only to the Columbia River, with the Klamath River another big California contributor. Driven by the Sacramento and San Joaquin river systems, the Central Valley nursed a ballpark average of a few million salmon per year, emerging each spring out of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, says Mantua.

“Today, natural production, maybe in a good year is in the hundred thousand or hundreds of thousands,” Mantua says. “So, yeah, it’s a few percent of the historical population.”

In addition to cold ocean water and an ample food supply at sea, salmon require cold river water that drains all the way to the sea, and, during their early life, a delta habitat. Salmon eggs do not survive in water warmer than 56 degrees, which is why adult fish ready to spawn instinctively head toward the cold, upper headwaters and tributaries coming out of the snow-packed mountains.

Development in the ’40s through ’60s, and especially the constructions of dams like the Shasta Dam, built in 1943 on the Sacramento River, played a key role in the near-annihilation of the long-standing fish stock. “When they built the big dams in California, they basically blocked off access to 80 or 90 percent of the habitat salmon historically used to reproduce in California,” says John McManus, executive director of the GGSA.

Fish ladders, which are like a staircase of pools that salmon can jump through to get over the dam and continue their journey upstream, were built on river dams in Oregon and Washington.

“Well, in California when they built dams, they didn’t put a ladder on a single one of them,” says McManus. The problem with building them now is that most of the dams in California are too massive. “A fish ladder will work with a dam that’s up to about 140 feet high,” says McManus. “The dams that we have in California, a lot of them are in the 200-feet-plus range. Now, everybody is forced basically to get along in the valley floor, in whatever habitat’s left over,” says McManus. “It’s kind of a wonder they’re still alive. They’re clinging to existence.”

One solution being discussed on the Yuba and Sacramento rivers is a “trap and haul” plan, which would trap adult salmon who beat their heads against the base of the dams, and give them a ride up over the dam in an elevator, then trap and truck the baby salmon who come back down the river after they’re hatched. But it’s an expensive proposal, says McManus. One such program that may begin at the Shasta Dam in two years is estimated to cost $16 million for the first three years, according to the federal Bureau of Reclamation, which manages Shasta Dam.

California’s four salmon runs—Fall, Late-Fall, Winter and Spring—are named for the time of year they return from the open ocean as adults, after about two to five years spent feasting on smaller fish and krill at sea, and back under the Golden Gate Bridge to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. As of 1989, the winter run had joined the ranks of 130 other endangered and threatened marine species when it was listed as an endangered species under the Federal Endangered Species Act. Ten years later, the spring run was listed as threatened.

It’s the state’s numerous hatcheries, managed by the California Department of Fish and Game, that now propel the strongest fall run, which makes up the bulk of California’s fishery. Not to be confused with farmed salmon—a practice banned for salmon in California—and a far cry from the on-land GMO-raised salmon recently approved by the FDA and projected to hit supermarkets in two years, hatcheries produce about 90 percent of chinook salmon caught in the ocean. But hatcheries are not invulnerable to drought conditions or massive habitat losses in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

“When we have a really good fishing year out in the ocean, it’s because of two things,” says McManus. “We have a good contribution from natural spawning salmon coming out of the Central Valley, and we have a good contribution from the hatcheries.”

Feast or Famine

When I ring Frank Ribeiro’s boat, Gayle R, in the Santa Cruz Yacht Harbor, his answering machine squawks out that there is “no new news!” With an email list of more than 1,000 customers for salmon and Dungeness crab, which he’s been fishing locally since ’71, everyone is clamoring to know if crab season will be called back on. I found Ribeiro—whose reputation as both a damn good fisherman and a notorious flirt echoes up and down the docks—on his boat, cooking a pot of beans. Sitting on the deck, he jokes to a passerby that he’s going to bottle and sell the rain water he’s been collecting in plastic bins when water is scarce this summer. “Like when they canned San Francisco fog and made a killing selling it as souvenirs,” he says. “I’ve got to make a living somehow.”

Last year, Ribeiro took the salmon season off. “There were some fish up north, but not much down here. They said it was going to be a bumper year, but it wasn’t,” he says. “We haven’t had any water in the rivers. They claim that there is a lot of fish trying to go up the rivers, but we don’t know what’s going on. We won’t know until we go fishing.”

If you can catch 200-300 pounds of fish, you can make a living, he says, and if you can get more than 1,000 pounds you’re pretty much set. “I’ve done OK,” he says, pausing to greet E dock’s resident seagull, P.P. “I’ll always fish, as long as I’m alive.”

With a house in the Azores and one in Santa Cruz, Ribeiro, now 70, represents a generation of old timers who weathered both good and bad years, but for whom the good years outnumbered the bad.

“When I first started, the piers were loaded,” says Wilson Quick, who began fishing out of Santa Cruz in 1966 with his dad, and continues to fish for salmon up and down the coast on his boat Sun Ra. “All of that stock was nothing but a solid commercial fleet. I would say there were at least 60 salmon boats in the Santa Cruz harbor in the beginning.”

Today, there are 25 boats with commercial salmon permits, according to Hans Haveman of H&H Fresh Fish Co., who has also been the official fish buyer at the Santa Cruz Harbor for the past three years.

Following a period of abundance in the late ’80s and then again in the late ’90s and early 2000s, California’s salmon season was closed in 2008 and 2009, due to a population crash that scientists at NOAA in Santa Cruz found was due to a lack of upwelling and the subsequent low production of krill, one of salmon’s dietary staples.

“The population has undergone a modest rebound since then, but it still has not reached the abundance that we observed in the late ’90s and early 2000s,” says Michael O’Farrell, a research fish biologist at NOAA.

“To be honest, I haven’t had a good year since I have taken over. Even from last year, being a decent year, there was barely enough for my farmers markets,” says Haveman, whose top-selling fish at H&H is salmon. “It’s sad because it used to be what everybody put on their barbecue, and in the last couple years it’s turned into a ‘birthday fish,’ as I call it, because people can only buy a little piece of it at $25 per pound.”

The inception of farmed salmon during the abundant ’90s had a huge impact on local fishermen, whose price was brought down to 97 cents per pound, says Haveman. “Now it’s come full circle. People learn more about farmed fish, and they’re breaking down the door for wild fish,” says Haveman, who says prices are now around $5 to $8 per pound off the docks.

According to McManus, California’s salmon fishery, currently estimated at around $1.4 billion and employing 23,000, would be more like $6 billion if abundance was restored to 1988 levels. “And that money gets spread all over; it’s the guy at the fuel docks who’s getting money for fuel, it’s the guy at the boatyard who had to fix your boat, it’s the guy who sells the trailers, runs the harbor, fishing equipment,” says McManus.

About 60 percent of salmon caught in Washington and Oregon are Central Valley fish, he adds, so it’s not just our economy that gets hurt during bad fishing years.

While Quick says he’s seen an increase in small sardines, a potential good sign for salmon, Greg Ambiel, who has been fishing salmon locally for 30 years, is not hedging any bets for this coming season.

“The fish are being killed in the Central Valley before they get a chance to get to the ocean,” says Ambiel. “If you follow the money, that’s who gets the water. It’s simple, just go look at the almond trees in the Central Valley.”

Indeed, over the last few years, a fairly drastic shift has occurred, with high-profit almond crops replacing raisin grapes and other less profitable crops in the Central Valley. The problem for salmon is that it takes a gallon of water to produce one almond—which is three times more water than it takes to produce a grape—according to a study published in 2011 at the University of Twente in the Netherlands. Water demands for agriculture are a known contributor to an estimated 95 percent loss of salmon’s critical rearing ground in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

The success of the 2016 season also relies on the survival rate of the juveniles who went to sea in the spring of 2014. “That was a transition year from what looked like really good ocean conditions in 2012, 2013, the spring of 2014. But by the fall of that year, it started to look really bad,” says Mantua, who says ocean temperatures remained warmer than normal for all of 2015, which is not favorable.

Two weeks ago, O’Farrell began the process of calculating 2016 abundance forecasts for both the Sacramento and Klamath rivers and tributaries—based on data that includes the return of fish the previous fall. Each March, he reports the number to the Pacific Fishery Management Council, who then sets the season in April.

“Where we’re at right now, we’ve come out of the very low abundance periods of 2008 and 2009, but we don’t know exactly what the returns are for this past year,” says O’Farrell. “There are some issues that we are monitoring with regard to the effects of drought and ocean conditions. It’s hard to say which way the population’s going to go at this point, but we’ll have more information on that in a couple of months.”

Hatch-22

Under ideal conditions, a hatchery will produce a lot more juvenile salmon smolts that are ready to go to the ocean from a single pair of parents than could be produced in the wild. “Wild fish are spawning in gravels—some of those eggs may not get fertilized, some are going to get preyed upon by other fish or birds, some might not successfully hatch, and then once they hatch, the fry are going to be subject to lots of predation risk. So a lot of those fish end up getting eaten before they are big enough to go to sea,” says Mantua. “For a pair of natural spawning salmon, maybe in a really good year they’ll produce 50 or a hundred smolts, but for a pair of spawning adults in a hatchery, they might produce 5,000.”

But drought can tip those odds considerably: for the past two years, 95 percent of winter-run salmon were killed off by low water levels and high temperatures in the Sacramento River, and 98 percent of salmon eggs perished in the Red Bluff area this year. The drought also left Lake Shasta at low levels. Such conditions that hurt the winter run are not good for the other runs either, says McManus.

Heavy rains not only raise river levels to help salmon down the river, they also raise water turbidity, which acts as a cloaking device against predators. The last year that happened was in the winter of 2010-2011, says McManus. “It started raining in October, and it didn’t really stop until June. So, in a situation like that, in spite of the dam, there’s so much water everywhere that it mimics the way it used to be in the good old days before the dams,” he says. “In fact, you get a bunch of runoff coming down even below the dams. So in situations like that, survival of the juvenile salmon is quite high.”

In 2014, to avoid high loss of baby salmon due to low, clear water conditions during drought, the GGSA began encouraging all of the state’s hatcheries to truck their productions down to the bay to release them safely. Of five major hatcheries, which collectively produce around 32 million juvenile salmon, says McManus, two were already trucking 100 percent of their production, and by 2015, GGSA had gotten the other three to also give their smolts a ride—which is expensive.

“The biggest hatchery we have in the Central Valley is called the Coleman Hatchery, up by Redding,” McManus says. “It produces 12.5 million juvenile salmon every year, and it’s around 280 miles from the Bay. You can fit about 120,000 in a tanker truck, so if you think about it, that’s over 300 truckloads.”

This means there could be a fairly good chunk of hatchery-produced salmon out in the ocean this year—and old enough to be fished—as a result of the 2014 trucking, says McManus.

But while scientists and fishermen agree that trucking prompted an increase in survival, Steve Lindley, leader of the Fisheries Ecology Division at NOAA, says that the practice is the only GGSA-backed idea that his lab does not agree with.

“We have serious concerns about the longterm consequences of those practices for the genetic integrity of the stock,” says Lindley. When salmon make their way down the river on their own, they use their sense of smell to memorize their way back. “When they’re trucked, the fish can’t find their way back to where they were born very accurately, and they end up going all over the place, and they interbreed with each other.”

Inbreeding is especially detrimental to endangered fish, whose low numbers increase the probability. “It causes fish to die before they can reproduce,” says John Carlos Garza, a research geneticist at NOAA. Garza, who was recently dubbed “The Fish Matchmaker” in the New York Times, is currently working to provide DNA-based elucidation of kin relationships to conservation hatcheries. In the wild, salmon are more likely to recognize close kin to avoid breeding with them. “In the hatcheries, typically, it’s a haphazard process,” says Garza. “They’re sticking this big bucket into the tank, and taking whoever comes up first in line, first male, first female.” The genetic markers involve a noninvasive fin clipping, and is especially important for small hatcheries. “It essentially adds back in the element of inbreeding avoidance that occurs in natural populations to the hatchery environment,” he says.

Restoring Hope

While the Central Valley Improvement Act, passed in 1992, ambitiously hoped to double the number of salmon and steelhead trout in the Sacramento River basin over the past 22 years, they’ve fallen short. While their goal was to see 86,000 spring-run chinook salmon spawning in the Central Valley by 2012, the number was just 30,522. Federal officials cited obstacles such as drought, competing demands for water and lack of funding.

But Lindley points to success stories in Central Valley wetland restoration in places like Clear Creek and Butte Creek. “These shallow areas that are nurseries for salmon, those populations have done very well, even during the poor ocean and drought periods,” he says. “So it’s not a lost cause. But we do really need to address some of these habitat issues, and find a way to operate salmon hatcheries in a way that supports our fisheries without imperiling their long-term liability. We’re really keen on working with GGSA and the fishing community and the broader fish and water communities to try to find those kind of solutions.”

The GGSA is also working with researchers at NOAA to identify areas of high predation along the river and delta, to try to restore some of the historic rearing areas where the fish can pick up weight and size and find refuge from predators.

“The public awareness is basically the water issues in the Central Valley,” says Haveman. “This is the most vital resource and everybody can access here in California, and it starts in that river system and ends on the dinner plate.”

Lindley thinks that the California WaterFix plan is a step in the right direction as far as making the state a little more resistant to drought and helping revive fish populations. The $20 billion program would utilize pumps and tunnels under the delta that would allow water to be taken out more efficiently. In the current system, a large amount of freshwater is pumped into the delta during the summer months to keep saltwater out, which is not only a waste of water but creates a big lake-like environment for freshwater fish to eat juvenile salmon, says Lindley.

There has been success on the Columbia River since 2005, when water managers were required to begin opening the reservoirs every springtime, says McManus.

“It’s worked wonders. The salmon runs in the Columbia River have rebounded big time. And it’s because of this runoff, it’s artificial runoff but it mimics natural runoff, and it functions exactly the same way. It carries the baby salmon in that camouflaged turbidity rapidly down the river, which is all you need,” McManus says. “So, in California, if we had something like that we would see a real beneficial result, rapidly.”