From unique children’s playhouses to full-fledged homes, we take a look at impressive treehouses that call Santa Cruz County trees home

From unique children’s playhouses to full-fledged homes, we take a look at impressive treehouses that call Santa Cruz County trees home

On a recent evening, after a wrong turn led to a precarious drive up a bumpy, rock-strewn dirt road, I arrived at the idyllic Corralitos property of Mary Jane Renz.

Catty-cornered from a traditional red and white barn and past a chicken coop was the trailhead that would lead me to my destination: the family’s cozy studio, which happens to be a dozen feet off the ground and supported by three second-growth redwoods.

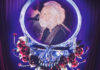

A short hike in the darkening dusk later, there it was, glowing in a shadowy grove—the simply named Redwood Treehouse.

A bridge leads from the trail to the front deck, where an ashy-colored cat named Grey is on constant lookout. Inside is a surprisingly spacious guesthouse, with a fireplace, bed, kitchenette and bathroom. “It has everything. People often say they thought it was going to be good, but they didn’t think it’d be this good,” says Renz, who, in addition to having family and friends stay in the treehouse, uses the space to make products for her company, Heaven and Earth Body, lending the one-room studio a faint herbal aroma.

The treehouse was built and then lived in for several years by a stained-glass artist named Randy Beaver, who called the dwelling The Fogship Beaver. Renz’s family bought the land and its accompanying treehouse, which they renamed, about four and a half years ago.

A photo album plucked from the treehouse’s bookcase tells the story (a love story, as it turns out) of the dwelling’s three-year making. On a nearby windowsill sits the 2004 coffee-table book “Treehouses of the World,” by Peter Nelson, the undisputed king of remarkable treehouses.

A photo album plucked from the treehouse’s bookcase tells the story (a love story, as it turns out) of the dwelling’s three-year making. On a nearby windowsill sits the 2004 coffee-table book “Treehouses of the World,” by Peter Nelson, the undisputed king of remarkable treehouses.

Nelson started an annual Treehouse Conference in 1997 with Out ‘n’ About Treesort owner Michael Garnier. The latter is the namesake for the Garnier Limb, a contrivance known to those on the treehouse circuit as “GL,” and which Nelson writes is “unquestionably the most important technology to come out of the Treehouse Conferences.” The “turned-steel limb” is screwed into a tree trunk, allowing for larger, heavier and sturdier structures to be placed in trees, more safely.

The apparatus is partly responsible for the modern treehouse renaissance, which is characterized by unique and impressive feats of carpentry that give the Swiss Family Robinson a run for its money. The roots of these elaborate reincarnations can be traced back to jungle tribes who lived in trees to avoid predators, scavengers, poisonous critters and violent neighboring tribes. (The Korowai, of New Guinea, still keep their houses atop 40-meter high trees to remain safe from a nearby tribe of headhunters called the Citak.) Treehouses as we know them appeared in vogue across Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries as both playhouses for children and cafes and gathering spaces for adults.

In addition to the GL, treehouses ascended in popularity in recent years thanks to the Internet, which made it possible for people to post photos and stories of treehouses they have built or visited, catapulting the ancient structures from something that mostly existed as backyard secrets to a hot topic catalogued in slews of coffee-table books, blogs, television episodes and magazine features. Riding this wave, Nelson is following his many books on the subject with a new TV show, “Treehouse Masters,” which premieres on Animal Planet at 10 p.m. on Friday, May 31.

Although the network recently contacted the Santa Cruz County Conference and Visitors Center to see about filming an episode (in which Nelson helps a family or business build a treehouse), no local installment had been planned as of press time.

But Santa Cruz County, with its hearty forests and arboreal neighborhoods, is a natural fit for treehouses. One needs only to remember to look up to realize that these enchanting structures are everywhere. For locals, they are, of course, a space to play and hide; but they are also an outlet for creativity, a place to call home, and, even, a means of taking a stand.

As I settled in for a quiet night at the Redwood Treehouse, I pondered Nelson’s words from the opening chapter of “Treehouses of the World”:

As I settled in for a quiet night at the Redwood Treehouse, I pondered Nelson’s words from the opening chapter of “Treehouses of the World”:

“The fantastic allure of being up in a tree refuses to recognize cultural or geographic boundaries, just as it renders age and gender irrelevant.”

Branching Out

At least one Santa Cruz treehouse has made it into a Nelson book: a nearly 400-square-foot office built on commission by Santa Cruz County Builders owner Thomas Kern in 1999. The Boulder Creek building is perched 50 feet up in a redwood and is reached by a suspension bridge that’s 42 feet high.

The domicile cost its owners $35,000, which Kern says was “pretty much a break-even job in terms of labor and cost of materials.”

“That’s a lot of money to spend on what’s basically a glorified tree fort,” he says, “but if you’ve got the money, what a great way to spend it.” (The tree bungalows Nelson builds range from $90,000 to $150,000 a pop, and his new show, “Treehouse Masters,” promises to feature even more extravagant abodes.)

Construction was a challenge, to say the least—particularly before the platform was built and there was nothing to sit or stand on—but Kern reveled in the opportunity to do something different and creative. In the years since, he has been itching to build another.

“This is a prime area to build treehouses in, and yet there aren’t many doing it [on this scale],” says Kern. “I would do one in heartbeat.”

So would general contractor Nick Mitchell. He has built a handful of treehouses of varying design, including an artistic 14-by-14-square-foot tree deck in his parents’ front yard near West Cliff Drive. Since it was built five years ago, the tree’s droopy branches have grown down into a thick umbrella that shields the circular deck from street view. The only opening in the greenery is a patch intentionally kept clear so that Mitchell’s Cove can be seen from the deck. (The surf spot was named after his father, Al Mitchell.) Even though much of the materials were reused from past jobs, the supplies added up to around $3,000.

More extravagant is the two-and-a-half-story treehouse Mitchell made for a family in Bonny Doon. Most kids fantasize about treehouses worthy of Peter Pan’s Lost Boys, but in the case of these children, they got to see their dream realized.

More extravagant is the two-and-a-half-story treehouse Mitchell made for a family in Bonny Doon. Most kids fantasize about treehouses worthy of Peter Pan’s Lost Boys, but in the case of these children, they got to see their dream realized.

“I sat down with the kids before I sat down with the parents,” says Mitchell, stepping through the front door into the fully enclosed, round first floor. He retrieves a large clipboard with a child’s artistic rendering of the house clipped to it. “I gave them six treehouse books and said ‘mark everything you like, draw me pictures,’ and they did,” he says.

A stairwell provides access from the first to the second floor, where one can scamper up branch stubs to the third level deck, which boasts an extensive view of forest and the hazy blue of the Monterey Bay.

“All treehouses are built for adults and kids, alike,” says Mitchell, leaning against the railing, which he made with branches from the host redwood. “We’re all kids. We grow up, but hopefully you don’t stop being a kid.”

There’s something comforting about the fact that, when you are in a tree, you move with its subtle rhythms and sways, he adds.

Although Chandra Lila and her fiancé, Jay Duffy, built their new Midtown treehouse primarily for Lila’s two sons, they crafted it with grown-ups in mind, too. Both the young and young-at-heart have been enjoying the well-made fort, they say.

Duffy put his skills as owner of Seven Seas Carpentry to use constructing the treehouse (his first), and, like Mitchell and Kern before him, studied arboriculture to ensure the health of the tree. “You can definitely do it the wrong way,” he says.

The treehouse was constructed with 90 percent recycled materials in a pepper tree on weekends last summer. Before the roof was on, it was dressed up as a pirate ship for a birthday party (foam swords still rest against one wall)—a fitting decoration considering the nautical theme already present in Duffy’s work. For Halloween, the family put the treehouse’s position right above the sidewalk to good use, lowering candy down to trick or treaters as they approached the house. Lila calls it a “teahouse treehouse” because of Sunday afternoon tea parties she’s been having with friends.

“Everybody loves it,” says Duffy, moments after a neighborhood kid shouts up to say hello. “I have only gotten one [complaint] from a cranky neighbor who said, ‘It looks like the freakin’ Taj Majal.’” (The comment could also be taken as a compliment.)

“Everybody loves it,” says Duffy, moments after a neighborhood kid shouts up to say hello. “I have only gotten one [complaint] from a cranky neighbor who said, ‘It looks like the freakin’ Taj Majal.’” (The comment could also be taken as a compliment.)

Although theirs is in the more traditional vein of kids’ playhouses, Duffy believes that treehouses posses great potential for eco-friendly residential living, and hopes to someday build a habitable one. “It’s about maximizing your space, downsizing your crap, [and] realizing you can be happy with less,” Duffy says of the concept. “You’re having less of an impact on the earth not only with your carbon footprint but with your physical footprint, as well.”

Homes Up High

“Looking for a special person interested in filling our vacancy in the treehouse.” This ad was recently posted to the housing section of the Santa Cruz Craigslist, and went on to request that interested persons “must be good with heights and wind” as “ the house does shake violently when it’s windy.”

There was only one time in his five years of living in a treehouse that Corbin Dunn was inclined to descend from his arboreal home because of strong winds, but the whims of the weather were certainly a defining aspect of his experience. (Wind could often make it feel like being in a boat, he says.) Dunn garnered widespread attention by living in a treehouse on his parents’ Corralitos property from 1999 to 2004. He built the treehouse in a “fairy ring”—the circle formed by baby redwoods that spring up around an older, “mama” redwood—at age 20. (See next week’s cover story for a full feature on Dunn and his innovative projects.)

“I think it’s primeval,” he says. “You have this instinct as man to live with nature and also be safe from things that might attack you. Being up high in the trees makes you feel safe, like a bird in a bird nest.“

Dunn’s experience is becoming less uncommon, as treehouses are turned to as options in the tiny homes movement, says Greg Johnson, president of the Iowa-based Small House Society. Tiny homes are a green solution embraced by some as a way to reduce a household’s environmental footprint.

“The iconic image people connect with the small house movement right now are these traditional-looking homes that have been shrunk to the size of garden shed,” Johnson says. “But really the movement encompasses more than that—cottages, cabins, treehouses, and, to some extent, people living in small apartments.”

“The iconic image people connect with the small house movement right now are these traditional-looking homes that have been shrunk to the size of garden shed,” Johnson says. “But really the movement encompasses more than that—cottages, cabins, treehouses, and, to some extent, people living in small apartments.”

Treehouses are a natural fit for the tiny homes community, because they are DIY, off the grid, and alternative—all characteristics of the tiny homes scene, he says.

But the living arrangement has its obstacles, from cost and building challenges to accessibility and weather. Johnson has observed that many tree homes either exist in warmer climates or are used only seasonally.

Another hitch is that unlike traditional structures, treehouses, like small homes built with biodegradable materials such as straw bale, are not permanent. Dunn’s treehouse remained standing for five years after he moved out, when the flooring fell out during high winds. Full-fledged incarnations like the office Kern, of Santa Cruz County Builders, created in 1999 hold up well. But all of the builders who spoke to GT about their treehouse creations cited the need for ongoing maintenance and their ultimately ephemeral nature.

“In some ways it seems like a waste to spend time and money on something that won’t last,” says Johnson. “But for some people it’s OK to go to the beach and build a sand castle and know [that] the next day it will be washed away.”

Even when these factors are manageable for determined treehouses residents, the issue of their questionable legality remains an issue.

“One of the reasons [many] tiny homes are successful is because they are on wheels, so you can drop them on a piece of property and they are totally legal,” says Dunn, who says he had a friend ousted from a residential treehouse by the county. “Whereas if you build an equivalent square foot treehouse you’d have a lot more trouble on the legality side of it.”

Treehouses are legal and do not require permits if they remain, as usually intended, play structures. Things get complicated when a treehouse is used as a living unit, says Juliana Rebagliati, director of planning and community development for the City of Santa Cruz. adding, “The zoning code allows one single-family residence per lot in typical single-family zoning districts, and a single-Accessory Dwelling Unit with a permit.”

But treehouse issues had never come to the department’s attention, she says—until recently.

“In more than 20 years of collective memory at the Planning and Community Development Department, we have not addressed treehouses,” she tells GT. “In general they are considered play structures. There is one exception.”

Enter Claudine Désirée, a homeowner and substitute teacher best known locally for her expertise in building cob structures. Her Downtown Santa Cruz property is a mini “eco-village,” with a cob yoga studio, fruit trees, sauna, chickens and a treehouse. The latter came to be when the need for more space in their small home arose as her three sons got older. Seven years ago, Désirée—a self-described “earthy” person already interested in distinctive structures—looked up at the healthy oak in the yard and saw the opportunity for extra living space.

Free Skool Santa Cruz held a two-weekend workshop that got the treehouse under way, and Désirée enlisted the help of a carpenter friend to finish it. The compact, fully enclosed room became her eldest son’s bedroom for several years. He named it The Lorax Lodge.

“It’s amazing up there—very private, but there isn’t one day that goes by that people walking by don’t look up and say ‘Whoa, cool!’ and want to come up and visit,” she says. “It’s a neighborhood landmark.”

“It’s amazing up there—very private, but there isn’t one day that goes by that people walking by don’t look up and say ‘Whoa, cool!’ and want to come up and visit,” she says. “It’s a neighborhood landmark.”

The Blackburn Street fixture went on to serve as a rental for UCSC students and then, from summer 2011 to summer 2012, a vacation rental through airbnb.com, where it was one of the most popular local rentals. At just $65 per night for one person and $75 for two, Désirée says the treehouse was booked solid the whole year, bringing her $11,000 in much-needed income.

“It was the ideal thing for the adventurous young types,” Désirée says, adding that the treehouse had visitors from every continent. “Because Santa Cruz is such a tourist destination, being able to rent these sort of [alternative structures out] to travelers makes everyone happy. I brought tourists to Santa Cruz who may not have stopped here because they couldn’t afford a hotel.”

But some past incidents caught up with Désirée, including a downtown parking permit application that truthfully listed the occupant’s rental as a treehouse and a separate complaint from a begrudging former tenant.

“When we have someone living in any kind of building that’s not considered a living unit, and we get complaints, we look into it,” explains Rebagliati.

Last September, Désirée received notice from the city that she was violating codes and that the treehouse had to come down. Fine with discontinuing it as a rental, but not with taking it down, Désirée appealed. The treehouse’s many fans and former guests rallied when Désirée needed $500 to file the appeal, and gave more than 200 signatures for her to take to the three hearings that followed (several also attended the hearings in support). Ultimately, Désirée was allowed to keep the treehouse if she altered it so that it can’t be lived in in the future, and was made to pay a fine, as well as hotel taxes she owed from using it as a vacation rental.

Throughout the ordeal, the treehouse was boarded up. Now that it has finally been resolved, Désirée is hosting a grand-reopening party for the treehouse, now called The New Lorax Lodge.

“I wanted to have a party to celebrate and hang out with the wonderful people who helped,” she says. She’s putting her house up for sale so that she can travel the world helping create eco-villages, and the June 8-9 and 12-14 events (more info at cruzincob.com) will double as an open house for the unique property.

“I wanted to have a party to celebrate and hang out with the wonderful people who helped,” she says. She’s putting her house up for sale so that she can travel the world helping create eco-villages, and the June 8-9 and 12-14 events (more info at cruzincob.com) will double as an open house for the unique property.

Désirée believes the response from neighbors and guests to the treehouse’s troubles is a testament to how joyous these treetop hideouts make people feel.

Kern, of Santa Cruz County Builders, agrees, attributing their eternal appeal to their ability to make everyone feel young. “You feel like you’re getting away with something,” he says. “It’s a kid feeling. It’s not your house, it’s your fort. You feel like it’s a getaway and it feels special and it’s just a little hideout.”

After a snug and peaceful night at Renz’s Redwood Treehouse, I awoke to a morning thick with mist and a visit from Renz.

“People dream about treehouses,” she says, seated on the dewy front porch before a backdrop of dense canopy. “I bet you we all wanted one. I wanted to live with Swiss Family Robinson.”

This lingering childhood fantasy is part of the reason treehouses continue to capture the imagination (and hearts) of adults, who, whether they build them for their children, for themselves, for others, or simply visit one, return to the treetop hideouts with a sense of delighted nostalgia and long-awaited fulfillment.

The night before, the treehouse had emerged, twinkling, from a murky landscape of silhouetted trunks as I neared. That morning, as I crossed the bridge and walked away up the narrow trail, it receded into the mist, swallowed by the forest like a dream.

More treehouse pictures on GOOD TIMES treehouse slide show on Facebook >>>

Leafy Hideouts

Tiburcio Vasquez, one of “the most noted desperados of modern times,” in the words of the Chicago Tribune, used a treehouse in Santa Cruz as his hideout in 1892, according to “Bandido: The Life and Times of Tiburcio Vasquez,” by John Boessenecke. A century later, it was rumored (and later disproven) that a wanted murderer by the name of Jon Dunkle “lived in a canyon tree house in Santa Cruz, had joined hippies in Santa Cruz, was snatched, and murdered by a drug dealer over $200,” as detailed in the book “The Boy Next Door.”

Banana Slugs In Trees

At UC Santa Cruz, thousands of acres of forest and an endless supply of adventurous denizens have resulted in a long history of surreptitious student handiwork, including treehouses, particularly in the school’s less developed upper campus.

“These unnatural creations come and go, usually from neglect and the natural erosion of time and the elements,” explains writing lecturer Jeff Arnett in the foreword to “An Unnatural History of UCSC,” a student-written book that documents this tradition. “Students often reclaim sites they discover, alter them, and rename them long after the original builders have moved on.”

An entry in the book titled “Tree Houses: Wildlife in the Forest,” concludes, “While it is impossible to know when the UCSC forests were first used for a home up in the trees, it’s inevitable that students and other ‘guests’ will continue to build houses in the trees as long as there are trees to climb and grown-ups to avoid.”

The book doesn’t reveal specific locations for the various creations (from the Wiccan Circle to the Totem Pole), so as not to jeopardize their subversive nature. “Since these are unauthorized by the university,” writes Arnett, “we feared that the map might fall into the wrong hands and result in a systematic destruction of these sites.”

Rules aren’t the only threat to these wooded retreats; the school’s long-range development plan can quash them as it progresses. This was the fate for Elfland, a veritable playground of nature-inspired constructions and hideouts. Needless to say, students protested when Elfland was logged to make room for Colleges 9 and 10 in the early 1990s. But vestiges remain and students continue to craft new edifices. A video posted to YouTube in February, titled “Best Tree House Ever,” showcases a recent UCSC tree structure that the poster describes as a 300-square-foot platform set between four trees. From its purported 80-foot height, it has a 360-degree view of the forest, campus, city and coast.

Arboreal Activism

Local forests are no stranger to a more serious use for treehouses: environmental activism. In 2007, demonstrators embarked on a 13-month “tree sit” in redwood platforms above UCSC’s Science Hill to protest plans for a new biomedical facility (which is now there).

Several years earlier, a tree sit on the other side of the county attracted the local spotlight. Beginning in June 2000, activists associated with Earth First Santa Cruz embarked on what was known as the Ramsey Gulch Tree Sit. By tying it up with rope, they erected a multi-platform aerial village in a redwood forest above Corralitos, near Mount Madonna, that was slated for logging by the lumber company Redwood Empire. This was in order “to prevent the cutting down of those trees and raise awareness about logging issues in our area,” says a participant who went by “Manzanita.”

Although the trees in question were eventually logged, awareness was certainly raised. Manzanita estimates that more than 1,000 people participated in the demonstration, whether it was to “hike out food, spend the night, spend the week or just to see the trees.” At one point, he says he went a week without descending from the platforms, which included makeshift sleeping areas, a kitchen, bathroom (i.e. a bucket), and rope lines to move between trees.

An October 2002 San Jose Mercury News article called the Ramsey Gulch action “the first tree-sitting protest in Santa Cruz County’s history.”

Haunted Trees

Starting in the mid-1900s, youth from Santa Cruz’s Westside cavorted in a well-known tree fort directly above Evergreen Cemetery. “Westside kids all knew where it was,” says Donna Mekis, who was born in Santa Cruz in 1953 and  recalls playing in the treehouse above Wagner’s Grove—just one of many treetop hangouts from local lore—in the ’60s.

recalls playing in the treehouse above Wagner’s Grove—just one of many treetop hangouts from local lore—in the ’60s.

Little did they know they might have been messing with an angry Chinese ghost.

For the many Chinese who lived and labored in Santa Cruz starting in the mid-1800s, it was an important custom that their remains return to China. They were buried for 10 years, with a redwood plank used as a temporary grave marker, before their bones were collected and sent to their ancestral village in China. “When they couldn’t make it back to China and died here, they felt unfulfilled, cheated and angry, so they came back as hungry and angry ghosts,” explains George Ow, Jr. in a missive for the Museum of Art & History.

When Ow’s uncle, Chin Lai (also known as Mr. Mook Lai Bok), died around 1949, “there was no one to take care of his bones,” writes Ow. The redwood grave marker eventually began to rot where it was stuck in the soil and, at a date unknown, local kids found it and used it for a floorboard in their treehouse.

Intentionally or not, the treehouse’s creators placed the redwood board face down so that, throughout the fort’s many years of use, the inscription on the grave marker was preserved. This made for a pleasant historical discovery.

“We suspect Chin Lai’s spirit, who was roaming, made it so that his grave marker was found and could be exhibited,” reads Ow’s story, which is on display at the MAH. “I see his spirit smiling.”

Sibley Simon, who leads the museum’s ongoing restoration of Evergreen Cemetery, reports that the treehouse, which transitioned from a kids’ hangout to something less innocent over the years, is no longer there. “The treehouse and camps on the cemetery property were a part of clandestine use of the property for various purposes during times (even decades) when the cemetery and its surrounding woods were either wholly abandoned or not closely monitored by the limited number of volunteers involved,” he writes in an email to GT. “Most such activity has now been curtailed in our restoration efforts.”

But if it weren’t for the treehouse, Chin Lai’s grave marker would most likely not have become the only surviving wooden grave marker from Evergreen Cemetery’s Chinese section.

More treehouse pictures on GOOD TIMES treehouse slide show on Facebook >>>