Isaac Nieblas’ world changed when he signed up for a Chicano Studies class at Santa Clara University.

The son of Mexican immigrants, Nieblas grew up for a time in Arizona, where ethnic studies were banned from the public school curriculum during his sophomore year of high school. He never had the opportunity to learn about Mexican-American history, politics or literature, which created a disconnect he felt for his course material until he attended college—the first time in his life that he began learning about his own people.

“I felt I was studying who I was as a human,” says Nieblas, now a junior. “Learning about the Chicano revolution in the 1960s made me feel as though my concerns, my issues, my humanity were legitimate.”

Nieblas’ experience with ethnic studies is far from unique, but for the first time it’s being quantified. New research out of Stanford University shows clear academic benefits to ethnic studies.

Thomas Dee, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Education, recently tracked more than 1,400 ninth-graders enrolled in a pilot ethnic studies program in the San Francisco Unified School District. The students were enrolled in the course if they had a GPA below 2.0 the year before, meaning they were considered at-risk for dropping out.

Dee found that the students who took the ethnic studies courses, which focused on issues such as social justice, discrimination, stereotypes, and social movements in U.S. history, saw a boost in overall academic performance compared to their peers—and not just in the ethnic studies course itself. Ethnic studies students increased their attendance by 21 percent, credits earned by 23 percent, and cumulative GPA by 1.4 points, elevating them from failing grades to the B-minus/C-plus range. Some of the highest GPA gains were made in math and science.

“Learning about the Chicano revolution in the 1960s made me feel as though my concerns, my issues, my humanity were legitimate.”

While there have been many qualitative studies on the value of culturally relevant pedagogy, this is the first quantitative one.

“I’ll confess that when we first generated these results, I was incredulous,” Dee says. “If I was reading a study saying that taking the course increases GPA by 1.4 points, I would not believe that.”

While the results seem clear, the reason for the benefits may be less so. Dee attributes the value of ethnic studies to pedagogy. “It’s about having instruction that corresponds with the out-of-school experience of these kids,” he says. “It’s simply going to fit them better and promote academic engagement.”

Another explanation is what’s known as the stereotype threat, which theorizes that minority students underperform in the classroom because of anxiety stemming from the expectation of negative stereotypes. But through buffering, either by forewarning against stereotypes or providing external examples of the challenges people of color face, students can overcome the stereotype threat.

“When I look at the ethnic studies curriculum,” Dee says, “it has many of the active ingredients of these light-touch psychological interventions.”

Here in Santa Cruz, Eric Porter, a professor with UCSC’s newly created Critical Race and Ethnic Studies department, says the basic findings “make sense.”

“It provides a sense of self worth to students, understanding of how their groups exist in the world,” Porter says of ethnic studies.

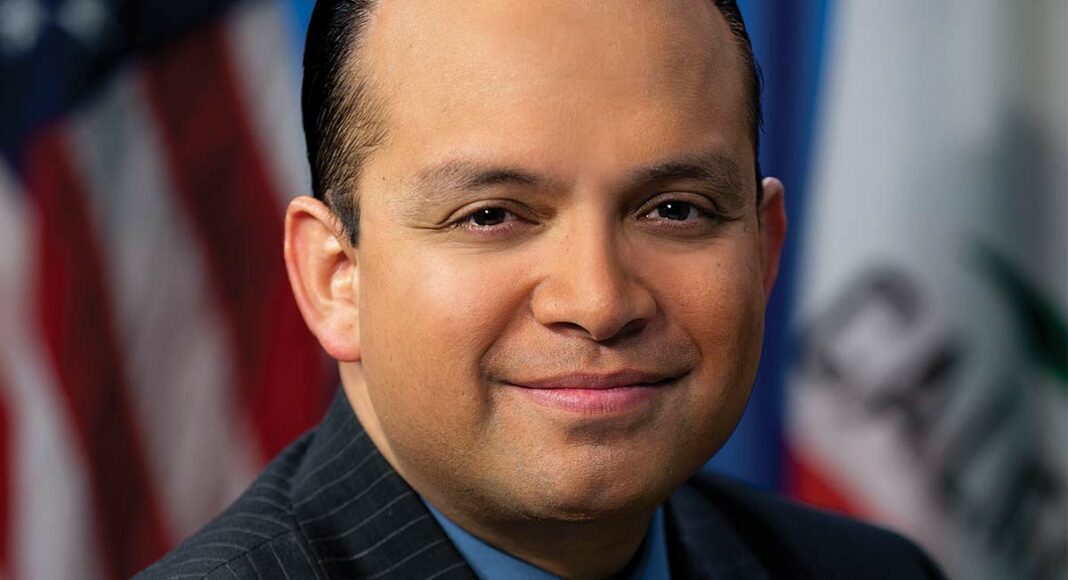

The study has made an impact in Sacramento, too. Last month, California State Assemblymember Luis Alejo (D-Salinas) introduced legislation that would require California high schools to create ethnic studies programs. Alejo, who also introduced similar legislation two years before, cites Stanford’s new report as newly minted support for the cause.

Despite the newly identified advantages to ethnic studies, the field has faced political challenges since its inception in the 1960s. Even though Santa Clara has one of the oldest ethnic studies programs in the country, Anna Sampaio, director of ethnic studies at Santa Clara University, says it still hasn’t been granted departmental status, and it still can’t offer a standalone major to undergraduates.

UCSC, meanwhile, has had a major for over a year, but no department. All of the major’s professors and staff share responsibilities with other disciplines on campus, like history or Latin American and Latino Studies. The first two critical and ethnic studies students are applying to graduate this quarter, and 12-18 will by the end of the year. Porter hopes to regularly graduate about 40 students per year in the major soon.

The seemingly sluggish embrace of ethnic studies is not entirely surprising. “Ethnic studies completely shifts the learning rubric,” Sampaio explains. “It says the center of the universe isn’t just rich, white, well-educated men. It can also be poor, working-class communities of color or women of color, and their voices have validity.”

Last year, Gov. Jerry Brown vetoed a bill authored by Alejo that would have required the California Department of Education to develop an ethnic studies curriculum for public schools.

Alejo notes that some laws he’s written—like the minimum wage increase and a bill to provide driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants—were carried for years by previous lawmakers before they finally passed and received the governor’s signature. Alejo is optimistic Californians won’t have to wait decades for the governor to sign an ethnic studies bill into law.

“We’re building a broad coalition—teachers, university scholars, teachers, labor unions and legislators—to convince the governor to do it,” Alejo says.

Santa Cruz City Schools don’t currently have an ethnic studies program, per se. The district does, however, support a Heritage Language class at all three high schools providing Spanish language instruction with history and culture studies for students whose first language is Spanish.

Elsewhere in California, some school districts are working to implement ethnic studies on their own. In 2014, Los Angeles approved plans to make ethnic studies a high school graduation requirement, and San Francisco and Oakland school boards voted to mandate that all high schools offer ethnic studies.

Nieblas argues that, given his own experiences, ethnic studies should be required starting in elementary school.

“I’m one out of 87 in my kindergarten class to make it to university,” he says. “If those other 86 could have seen themselves in the books—if they knew there was an Angela Davis, a Malcolm X, a Cesar Chavez—I think it could have made a ton of difference.

“I could be at this university with all of my childhood friends.”