In 1989, the World Wide Web was just struggling to be born, and the mobile connectivity that has remade the world’s economies and transformed human culture didn’t yet exist.

But what did exist was Marc Porat’s large red sketchbook.

Porat is the central protagonist in the engrossing new documentary General Magic, which plays at the Santa Cruz Film Festival on Friday, Oct. 11. In ’89, Porat was a young, Stanford-educated technologist and aspiring Silicon Valley visionary working at Apple.

In the film, Porat drags out his battered 30-year-old notebook. It’s what inside that notebook that gives the viewer a jolt, the shock of recognition in something relatively ancient, like seeing someone playing basketball in Egyptian hieroglyphics.

The drawings show what everyone would today recognize as a smartphone; it’s a sleek, pocket-sized device on which there are small icons representing apps for news, weather, maps, and shopping—a full 18 years before Steve Jobs stood on a stage and introduced the iPhone to the world.

“There comes a moment,” says Porat in the film, “when, for some reason, you’re in the future and you see something very very clearly. That’s what happened to me.”

General Magic, one of the highlights of this year’s SCFF, is the story of the Silicon Valley startup of the same name that had the right vision in the right place, but at the wrong time.

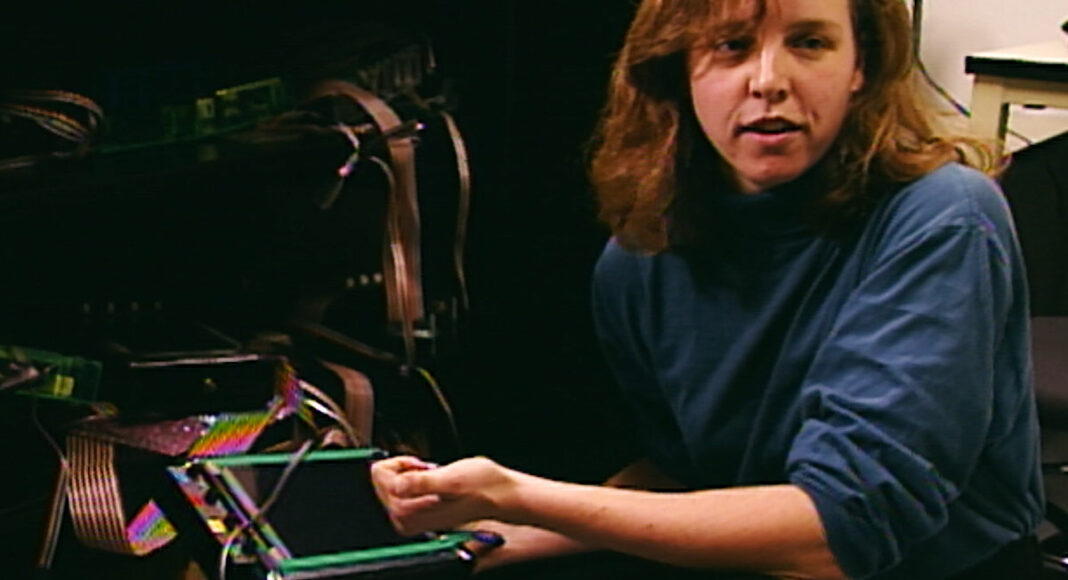

In 1990, Porat spun off from Apple and founded General Magic with the idea to produce his revolutionary device, which he originally called the Pocket Crystal. To do so, he enlisted a kind of technological dream team, which included Macintosh pioneer Andy Hertzfeld, legendary Apple engineer Bill Atkinson, programmer Megan Smith (who would later become the Obama administration’s chief technology officer), and many more.

The company failed. The Pocket Crystal morphed into the Magic Link, which was released in 1994, sold poorly, and quickly sank in the marketplace without a trace. The documentary makes the case that the vision was simply way out in front of the technology at the time. But the spectacular failure of General Magic laid the groundwork of the wireless world of today.

Though legendary in the office parks of Silicon Valley, the story of General Magic remains largely unknown to the wider public, even among the tech-savvy. Matt Maude, the film’s co-director with Sarah Kerruish, says in a phone interview that he had never heard of General Magic before embarking on the film project.

“When I first heard about it,” says Maude, “without even seeing the device itself, only the drawings of Marc’s concepts, this idea that you could fit in all of the functionality that an iPhone can do now into a device made for market in 1992 or ’93, that sounded to me insane. And that they were doing it with 1MB of RAM and 1MB of memory. It’s the equivalent of thinking about the 76KB that were aboard the (Apollo 11) lunar module. It’s just beyond belief.”

The film may not have been possible if not for the General Magic’s own in-house footage, mostly shot by Santa Cruz-based filmmaker David Hoffman in the early ’90s at a time when exuberance and enthusiasm were still abundant in the company’s Mountain View offices.

“We got in contact with a lot of people who had worked at General Magic and said, ‘Could you send us any photographs from that time?’” says Maude. “We were just amazed that people would send us ream after ream of photos. Every once in a while, we’d see someone else in a photo holding a camera and we’d get in contact with that person and ask for photos. And even, at one point, there was a guy in one of the photos holding a video camera. We found him, and he happened to have 300 hours of footage in a garage in Hawaii. That footage, combined with David’s, made the film.”

The old footage is balanced with present-day interviews with nearly all the central characters in the General Magic story. That includes former Apple CEO John Sculley, who emerges as the film’s primary black hat. Sculley—who had taken over Apple after the 1985 ouster of Steve Jobs—had encouraged Porat and supported the project until Apple released the Newton, its own hand-held mobile device, which the staff at General Magic considered a betrayal.

“We wrote to John,” says Maude. “We told him we were making a film about General Magic and we wanted him to be as candid as he could. He’s an antagonistic presence. People told us, ‘Why are you interviewing this guy?’ People think he’s an SOB across the entirety of Silicon Valley. But if you’re willing to own your mistakes and speak about them with regret and compassion, that’s a good human quality. I hope he has his moment and that people see him as three-dimensional.”

But clearly the most sympathetic character remains Porat, the leader of the revolution that came too early. In his 1990s public pronouncements about the General Magic vision, Porat exudes a Jobs-like aura of messianic confidence and computer-geek excitement. If Silicon Valley was built on companies with heroic and charismatic CEOs, Porat filled the role. However, the present-day Porat, like a retired ballplayer who never got that elusive championship ring, projects a vulnerable what-might-have-been wistfulness.

General Magic’s failure had many sources. The Magic Link device was a bigger and clunkier than Porat’s original vision. “It looks kind of like a Fisher-Price toy,” says Maude. Also, the company developed alliances with Sony and AT&T in the early days of the internet, when online worlds were still being marketed as closed systems (think ’90s-era AOL). By the time the internet had been liberated from such proprietary models, General Magic was slow to pivot.

Silicon Valley has transformed the idea of business failure, removing the stigma and recasting it as a kind of necessary tonic for later success. General Magic buys into that notion completely, even stating explicitly, “Failure isn’t the end. Failure is the beginning.”

Indeed from the ashes of General Magic rose the revolution that we are all living today. Tony Fadell, the inventor of the iPod and one of the pioneers of the iPhone, was a young General Magic go-getter and is interviewed in the film. Andy Rubin, who brought Android to the world, was also on staff. That’s 98% of the world’s cellphone market, spawned in one office.

Still, the film stresses, there was a price to pay. “It’s a strange kind of cliché that comes out of Silicon Valley, that failure is necessary,” says Maude. “But that kind of cutthroat business was not pleasant for anyone who experienced it. In fact, it’s really fucking painful for anybody who goes through it. If you’re going through it, where a company you’ve built or have been part of for years implodes, it’s devastating.”

When the film was finished, Maude and his collaborators invited more than 100 former General Magic staffers to a New York screening. “The cathartic energy in that room was ridiculous,” he says. “For a lot of those people, it was a failure, a black mark on their CV. For them to be able to walk away from (the film) and be like, ‘You know, that wasn’t a bad part of my life because it led to me being who I am now, or helped me understand how to create products today, that’s special. That’s all part of the story, too.”

GENERAL MAGIC

Playing at the SCFF on Wednesday, Oct. 9, at 2:30pm at the Del Mar. Encore screening: Friday, Oct. 11, 7pm, at the Colligan Theater. santacruzfilmfestival.org.