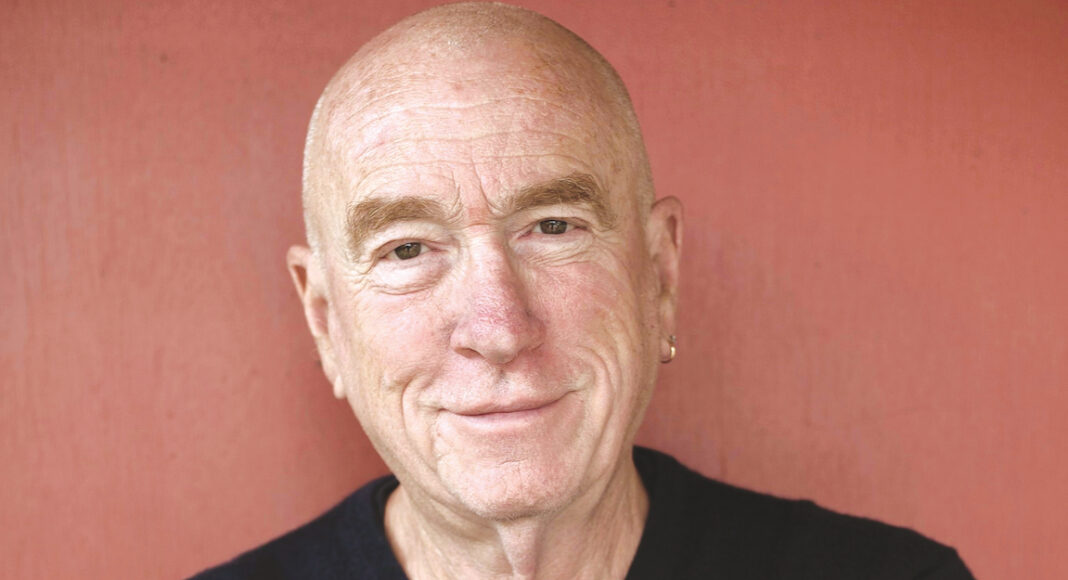

In Paul Skenazy’s new novel Still Life, new widower Will Moran makes tentative, seemingly aimless moves to rebuild his world. Gathering rocks and odd throwaways, he starts to draw and then paint these unlikely subjects. Obsessed with this project, he lets his house fall into bohemian disarray as unexpected intruders—some welcome, some questionable—disturb his solitude. Filled with sparkling dialogue, obsessive discoveries and a few flings, Still Life offers readers unexpected epiphanies.

What kick-started your latest book project?

PAUL SKENAZY: There are a lot of different elements that converged into what eventually became this novel. In 1978, I went to an exhibit of Georgio Morandi’s lithographs and watercolors. I remember it was on the top floor of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. I bought a poster from that exhibit that I still have on a wall in my living room. That began a lifelong obsession with Morandi’s work, and that’s where my protagonist, Will, came from. His last name, Moran, is my thank you to, and private joke about, Morandi. It has over the years made me think about obsessions—which ones we follow, and what they do to and for us. I started to imagine a book with almost no backstory: a guy locks himself away and starts to paint pictures on the walls of his house. Why? I didn’t want to know. Until eventually the character forced me to think about that. Which launched me into learning what story I had to tell.

Do you see ‘Still Life’ as a parable, a realist novella, or both?

I’m very much a realist in my thinking; almost a pedant about it. I can’t create a scene without a sense of the objects in the room, or in a park, or on a walk. If this novel is a parable, that’s a side effect. Still Life doesn’t have a moral, or point. It’s a story of one man in one town at a certain moment in time—a cranky, likable but at times unpleasant man who is in pain from his wife’s death—what he does to avoid that pain and how what he does transforms him.

Will, your protagonist, keeps a notebook into which he pours the puzzles that emerge as he rebuilds his life and embarks on obsessive/compulsive behavior. Do you keep a notebook?

I’ve tried to keep a notebook all my life. When I taught writing, I sometimes required, sometimes encouraged students to keep notebooks. But I’m erratic, always trying unsuccessfully to get myself back into one habit or another, like keeping a notebook. Will’s notebook came to me as a device to convey Will’s inner life while keeping much of it hidden—and also a way to muse about art more generally. It’s not a surrogate for me, except in that way that what we write always changes us. In retrospect, I realize that the deep substructure of Still Life comes from me thinking about aging, loss, grief, and what it means to live while others around you don’t. But saying that makes the book sound more maudlin and darker than it is. To me it’s a funny novel, built on awkward encounters that keep Will stumbling along and learning each time he falls and gets himself up—the way we do if we’re lucky enough to have experiences, and people around us to help us.

This book contains a rich sense of Santa Cruz as a place. Tell us about some of these settings.

There’s a way that place inhabits you as you inhabit it. Eudora Welty calls place in writing the “heart’s field.” I love Santa Cruz; it’s one of those great accidents of my life that I’ve had a chance to live here since 1971.

When you write about a place, you want to represent it in all its actuality. But you also want to explore its mystery, that feeling it provides that is unlike any other home ground. And exploring that mystery, you want to discover something new about where you are that you didn’t know before.

Kierkegaard wrote ‘Stages on Life’s Way.’ Your book might be seen as ‘Stages on Life’s Reawakening.’

I resist generalizing about life as a journey, or stages in our development, or even the sense that we move from path to path as we live. I am not who I was in my twenties or thirties, nor who I imagined I might be in my seventies. But I also don’t think I’ve made peace with those earlier mes, or with my present self. Maybe Will does, for a moment. It’s one of the gifts of art that it offers form and shape while life, at least as I know it, doesn’t. All I can do is try to tell Will’s story—offer a reader this particular adventure—and step aside.

Skenazy will read from ‘Still Life’ (Angel Press, 2021) on Zoom Forward Friday, July 16, with Ray Daniels and Thad Nodine (https://mailchi.mp/santacruzwrites/zoomforward to sign up).