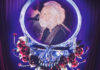

Las Cafeteras’ physical, exuberant sound and storytelling brings a traditional style into the 21st century

Las Cafeteras’ physical, exuberant sound and storytelling brings a traditional style into the 21st century

The members of Las Cafeteras are featured in the 2008 Oscar-nominated documentary The Garden, about Los Angeles activists attempting to save the South Central Community Garden from bulldozers—but don’t look for them on the soundtrack.

“We’re in there being beaten by cops,” says Hector Flores, a vocalist and multi-instrumentalist for the seven-piece East L.A. group, who will play a benefit for the Pajaro Valley Unified School District College Bound Scholarship Fund at the Mello Center on Friday, Jan. 30.

That was the year Las Cafeteras formed—straight outta Eastside Café, the L.A. “autonomous community space” which inspired their name—and at the time they were learning to play mostly straight-up Son Jarocho, traditional music from Veracruz, Mexico. Besides inspiring them as a political cause, their involvement with the South Central Farm Movement documented in The Garden turned out to be musically formative for the band, as well, thanks to Rage Against the Machine’s Zach de la Rocha. In support of the community garden, de la Rocha performed with Los Cojolites, a traditional group from Veracruz. The minds of Las Cafeteras were officially blown.

“We see Zach de la Rocha rapping over Son Jarocho, and he’s changing our world,” says Flores, the awe still in his voice.

Suddenly, the band was faced with a choice. “We were playing this traditional music, but we grew up listening to, like, riot grrrl music, and a lot of us went to hip-hop and listened to Tupac and Warren G,” remembers Flores. “We had to decide if we were going to mimic tradition, or create our own.”

Hearing their music now, it’s obvious which they chose. They call it “Afro-Mexican urban folk,” but it’s as radical in form as in political content. Their instruments include the jawbone of a donkey, the Carribbean marimbal (traditional to Son Jarocho, but also used in Cuban and Dominican music), and a wooden platform called a tarima on which members do some extremely percussive dance steps. Their music has a youthful exuberance and a unique, 21st-century take on a traditional sound, with (mostly Spanish) Spanglish lyrics.

Most people think they’ve never heard Son Jarocho, but actually they have. The most famous song to come out of the tradition is “La Bamba,” best known as a very, very old folk song sung at weddings in Veracruz until Richie Valens made it a rock hit in 1958.

Las Cafeteras do an updated version of the song, “La Bamba Rebelde,” which in the son tradition features reworked, personalized lyrics by the band referencing the Zapatistas, racist laws in Arizona, Chicano pride, and more.

“It survives, this song,” says Flores. “For us, it’s an anthem. We didn’t want to sing the ‘La Bamba’ of the past. We wanted to sing the ‘La Bamba’ of the future. We’re ‘La Bamba.’ We’ve survived.”

The band’s members were activists before they were musicians, but they see their music not as political (as it is usually labeled) but as based in telling true stories—their own stories, their families’ stories, their friends’ stories, the stories of the Chicano movement.

“We don’t say we’re political. We say we’re a real band,” says Flores. “My mom came across the river when she was 15. That’s not a political story. That’s my mom’s story.”

The band really doesn’t care what other people say about them. They never expected audiences to respond the way they have. They never expected their debut album, 2012’s It’s Time, to be noticed (and praised) by NPR and the BBC. They have simply been building what Flores calls a “culture of yes” in which they give each other permission to express themselves and experiment.

“We were never supposed to be here. We’re the band that never wanted to be a band,” says Flores. “We come with this DIY veracity and punk ethos, creating something out of nothing.”

Info: 7:30 p.m., Friday, Jan. 30, Mello Center, Watsonville. Tickets: $15/$18, 479-9421, snazzyproductions.com.