The summer of 1938 was promising to be an auspicious one for the seaside community of Santa Cruz. Well before the coming of the tourist season, newspapers across California were announcing a star-studded lineup of international swimming champions, races, acrobatic acts and Hawaiian musicians who would be convening at the Santa Cruz waterfront for a magical summer.

Headlining the extravaganza would be none other than one of the great Olympic athletes of all time—swimming legend Duke Kahanamoku, who was among the most famous sports figures in the world. The Duke had set countless world and national records, and had spectacularly won three gold and two silver medals in a trio of Olympiads, in Stockholm (1912), Antwerp (1920) and Paris (1924). At the age of 41, he was named as an alternate to the U.S. water polo team for the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles.

Moreover, he was widely considered the world’s greatest surfer, an international and regal ambassador of the waves.

As the Great Depression wore on into the late 1930s, and global war seemed imminent, Kahanamoku’s arrival in Surf City promised a bright light in a decade of economic doom and looming geopolitical darkness. By June of 1938, the Amateur Athletic Union in Honolulu had named an All-Hawaii swim team—composed of six men and three women—to join Kahanamoku on his California jaunt. Several venues from San Diego to Los Angeles to San Francisco were added to the Kahanamoku itinerary, with the Duke’s culminating California appearance slated for Santa Cruz on July 16 and 17.

By the beachfront’s booming Independence Day weekend, posters featuring the Duke were plastered throughout town proclaiming Kahanamoku’s arrival at the “Greatest Water Carnival Ever Presented.” The posters were both designed and composed by the Boardwalk’s legendary impresario Skip Littlefield, an inimitable one-man promotion machine, who had produced the waterfront’s famed Water Carnivals since the late 1920s.

“Witness in action the Greatest Swimmer of All Time, The Mighty Hawaiian Natator, Who Revolutionized & Astounded the Aquatic World for Twenty-five Years,” Littlefield’s poster declared. “Positively the Greatest Aquatic Show Ever staged on [the] Pacific Coast.”

Littlefield was a carnival barker at heart, and hyperbole ran through his veins. In a bylined article in the Santa Cruz Sentinel promoting his own event, Littlefield declared, “The arrival of the Duke signals the zenith in aquatic spectacles at the famed beach natatorium.” Locals were getting a glorious taste of the islands and Hawaiian culture, Littlefield asserted. “To seaside folk it seems in the light of present programs that the famous beach of Waikiki has moved in spirit to the Santa Cruz strand.”

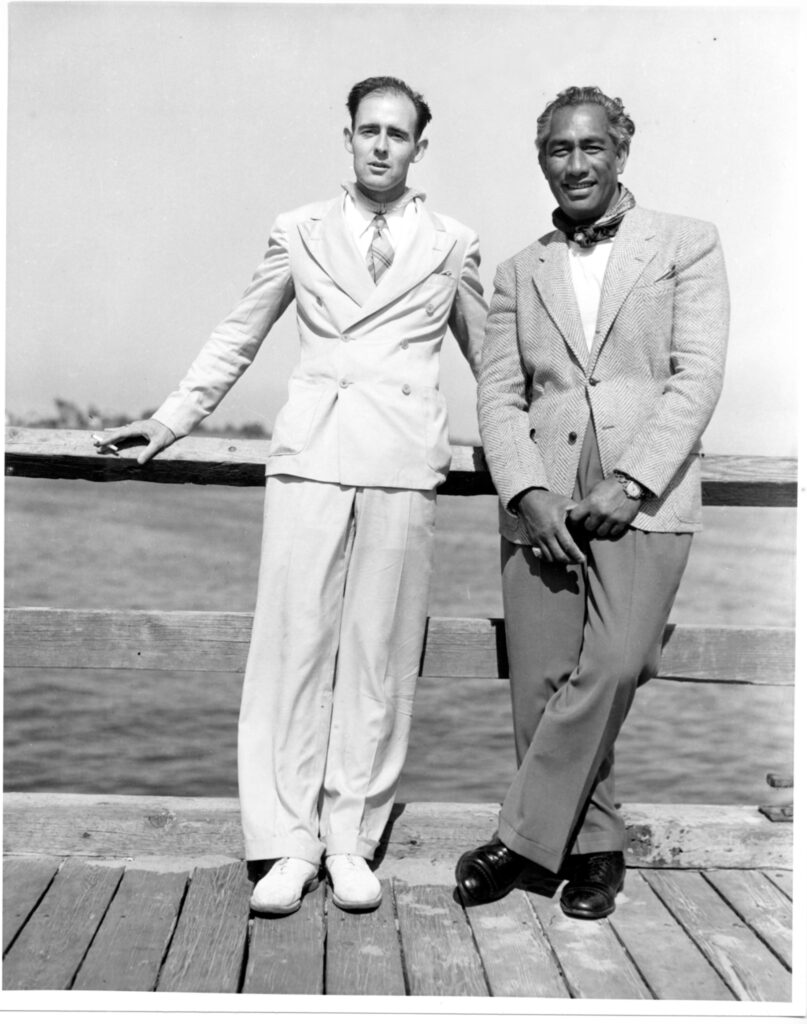

The Duke and his aquatic all-stars crossed the Pacific on the luxury ocean liner Matsonia and disembarked on June 29 in Wilmington, at the Port of Los Angeles, quickly making their way to San Diego for their first exhibition. They stayed three days in the southland, where the Los Angeles Times greeted the Hawaii contingent with banner headlines and large pictures of the Islanders practicing at the Olympic Swim Stadium, where a “model sports girls review” was woven into the competition—it was L. A. after all.

For the next two weeks the Hawaiians performed to swollen summer crowds, with a penultimate stop at the Del Monte Lodge in Monterey before their final jaunt to Santa Cruz. A huge banquet and awards ceremony was scheduled at the Palomar Hotel for Friday night, but at the last moment, the promoters in Monterey pulled a fast one, scheduling a second show on Friday (the demand for tickets had been enormous) and forcing a cancellation of the dinner Littlefield and the local Rotary Club had painstakingly planned.

“It was a great disappointment,” Littlefield told me years later, in his smoke-and-scotch saturated voice straight out of a Dashiell Hammett novel. “I can’t deny it. But the following nights produced two of the greatest aquatic shows this waterfront, or anywhere else for that matter, has ever witnessed. Standing room only! Spectacular!”

On Saturday night, a packed crowd witnessed new records set by Hawaiian swimmers at the Plunge—the massive salt-water pool that was part of the Boardwalk from 1907 to 1963—in the 50-yard freestyle and the 100-yard backstroke. When the Duke himself took to the pool, he showcased a number of freestyle techniques, including the Australian crawl and his own stroke that he developed during his teen years. He also, according to the Sentinel, exhibited “the art of paddling a surfboard without benefit of ocean breakers.”

Sunday, it was more of the same. By the time the weekend was over, the Hawaiians had set several new Plunge records and had come close to breaking world marks. Two young swimmers from Stockton also made their presence known, with Paul Herron setting tank records in the 220 and 440-yard freestyle races, and Fred Van Dyke taking two seconds off the standing record in the 100-yard backstroke.

But perhaps the most significant historic event of Kahanamoku’s visit took place away from the Plunge, on a surf break south and west of the Main Beach, though precisely where on the coast remains uncertain.

Front-page headlines in the Sentinel declared that “Santa Cruz Will Break Out Surfboards for Hawaiians,” reporting that “Surfboard riding off the breaker lines of Santa Cruz by Duke Kahanamoku and his golden merrymen from Hawaii is expected this weekend to bring a flood of newsreel cameraman and a flood of heartening publicity for this city.”

Ever since the famed three Hawaiian princes—David Kawananakoa, Edward Keliiahonui and Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana’ole—first surfed at the San Lorenzo Rivermouth in 1885, Santa Cruz had a fledgling but persistent surf culture that would come to full fruition in the late 1930s and early 1940s with the Santa Cruz Surf Club, whose members would include the likes of Harry Mayo, Bob Rittenhouse, Doug Thorne, Bill Grace, Hal Goody and Don “The Mighty Bosco” Patterson, the latter of whom was also a perpetual star in the Boardwalk’s Water Carnivals.

It was reported that a “long Philippine mahogany board was procured for the Duke during his visit here, and several other hollow-type boards will be pressed into service for other members of the Hawaiian swimming delegation.” Many, if not all, of the boards had come from members of the surf club, and other non-members such as Leland “Scorp” Evans and Andy Caviglia who had made their boards in a Santa Cruz High woodshop class earlier in the decade.

Evans later told surfing historian Kim Stoner and I that he had ridden with Duke and other members of the Hawaiian contingent on a break west of Cowell’s Beach (he actually pointed his arm in that direction), which I assumed was a reference to Indicators. However, Herb Scaroni, a pioneer North Coast rancher, told Stoner that Duke and the local contingent actually surfed the break at Four Mile, just down the coast from his family’s old dairy ranch.

Unfortunately, the newsreel footage of the Duke’s surfing expedition referenced in the newspaper accounts has never been located, nor have any photographs, so the precise 1938 Kahanamoku surf spot remains something of a mystery. The closest we’ve come is Evans waving his arm toward a phantom direction of his memory.

Duke Paoa Kahinu Mokoe Hulikohola Kahanamoku was born in Honolulu in 1890, a politically tumultuous time for his native island nation. Within just a few years of his birth, U.S. business interests—with the backing of the U.S. government—staged a coup d’état against the Kingdom of Hawaii, then presided over by Queen Liliʻuokalani. The Americans established a temporary government, with the primary purpose of protecting their business interests, and following a shameful political Keystone Cop routine of unbridled imperialism, the U.S. formally annexed the islands in 1898, establishing Hawaii as a U.S. territory, and by 1900, making the 10-year-old Duke an American citizen.

While he claimed indirect lineage to King Kamehameha I, “Duke” was neither a nickname nor an official title, but rather the given name of his father, who had been bestowed the appellation after a visit to the islands by Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh. As a boy, according to his biographer David Davis, his family and friends called him Paoa to distinguish him from his father (who worked as a police officer in Honolulu).

An uninspired student throughout his youth, Duke excelled in childhood games and physical activities, both on land and in the Pacific waters surrounding his homeland. By the age of four, he was an avid swimmer, and soon began to dive, body surf, board surf, sail and handle his position paddling an outrigger canoe. He also excelled in football, baseball (a popular sport in the islands) and boxing.

Kahanamoku’s great love, however, was always at the beach at Waikiki, where great and well-formed waves rolled in daily from several different breaks as far out as a mile from shore. As a result, the young Duke developed a freestyle stroke that made him the best swimmer of the Waikiki beach boys, who had revitalized the art of surfing.

In the summer of 1911, the Duke was timed in the 100-yard freestyle in 55.4 seconds, crushing the existing world record. The haole officials in the Amateur Athletic Union centered in the U.S. mainland refused to honor the time, claiming that Kahanamoku must have been aided by Pacific currents or imprecise watches.

A year later, Kahanamoku put those myths to rest. In February of 1912, he boarded the SS Honoluan for San Francisco and continued by train to Chicago (along the way he would see his first snow), then on to Pittsburgh and New York, where his swimming performances in a variety of meets would earn him a spot on the U.S. Olympic team in both the 100-freestyle and the 4×200 relay.

Duke’s arrival on the East Coast in the middle of winter presented a myriad of challenges for him. He was used to swimming outdoors, in the ocean, without the confines of a swimming pool. He had to learn to navigate a completely foreign culture, not to mention split-second turns in a concrete pool. His life and virtually every movement on the mainland was dictated by a clock; not by the rhythms of nature, as they had been in Hawaii.

By the time he got to Stockholm, Sweden, site of the 1912 Summer Olympics, he was ready for his first shining moment on a world stage. In an outdoor facility constructed specially for the Olympics in Stockholm Harbor, and with King Gustaf V and his wife Queen Victoria in attendance, the 21-year old Kahanamoku cruised to an easy victory in the 100 meter freestyle, setting a new world’s record and winning a pure gold Olympic medal.

He later picked up a silver medal on the 4×200 U.S. relay team—which lost, despite a gallant effort by Duke, to an Australian team that also set a world record in the event. And he apparently attempted a surf session in Stockholm’s Strommen River, a relatively unknown event that was recorded at the time by the Stockholm newspaper Dagens Nyhet. Kahanamoku had begun what would be a lifelong career as an ambassador of surfing around the globe.

In the aftermath of his initial Olympic glory, Kahanamoku—with his dark thick hair, handsome bronzed features and million-dollar smile—became a worldwide media darling. He was invited to swimming exhibitions in Moscow, Algiers and Hamburg, then back across the Atlantic for a surfing exhibition in Atlantic City, where the Duke first introduced the sport of kings to the eastern seaboard. Thousands of visitors crowded in to Atlantic City’s Steel Pier to witness the event.

The following year, he travelled back to California—this time as a destination, not a pass-through, as it had been on his way to his first Olympic tryouts. During the summer of 1913, he absolutely dominated swimming meets at San Francisco’s famed Sutro Baths as well as at the city’s Olympic Club.

During the final week of July, Kahanamoku and an Hawaiian swimmer identified in newspapers throughout the west as “Bobby Kawaa” ventured to Santa Cruz, where they raced in the Plunge before standing-room crowds of more than 2,000 spectators (Kahanamoku set a world’s record in the 50-yard freestyle), and also gave exhibitions in surfboard riding.

Despite claims by various surf historians that Kahanamoku had surfed in Southern California in 1912, this would have been Kahanamoku’s first recorded account of surfing on the West Coast. While in Los Angeles earlier that month, Kahanamoku had told a reporter for the Los Angeles Times that the waves in Southern California weren’t strong enough to ride. He was looking for a little surfing “to remind him of home.”

Apparently he and his partner found some surf here. On Monday, July 28, the Evening News reported that “Bobby Kawaa gave fine exhibitions of surf riding and presented his surf board of the tournament to Manager Wilson of the Casino.”

The 1916 Olympics, slated for Berlin, promised to feature a 25-year-old Kahanamoku in his athletic prime, but were cancelled because of the outbreak of World War I. In 1920, Kahanamoku, on the eve of his 30th birthday, was again selected to represent the Olympic team in a pair of races slated for Antwerp, Belgium (a city severely damaged by the carnage of the Great War).

On his way to the Olympics, Kahanamoku and six other members of the Hawaiian swim club arrived in Santa Cruz and participated in races at the Plunge. Kahanamoku dominated his signature 100-meter freestyle, while his teammates won most of the other races as well. Once again, the Duke and his colleagues took to the surf.

“The … Hawaiians attracted much attention Sunday after the swimming meet,” the Sentinel reported, “when they came outside and for a time were riding on the breakers, at which they are adept. They were seven in number, and after finishing their engagement on the coast are to go to Chicago for the tryout for the great athletic meet at Antwerp.”

This time, the Duke emerged with a pair of gold medals in the Olympics, setting yet another world record in the 100-meter freestyle and this time claiming first place on the 4×200 relay team.

Kahanamoku’s Olympic victories following the brutalities of World War I made him an international celebrity. He toured Europe to widespread acclaim, then returned to Hawaii, where he was received as royalty, but spent frustrating days seeking out a living in Honolulu catering to Waikiki tourists. A few years later, he moved to Los Angeles, where he tried his hand at a movie career (he had bit parts in several films) and finally discovered Southern California waves to his liking.

In 1925, using a surfboard, he rescued eight men from a fishing vessel that had capsized off Newport Beach. That effort led to many life guard units—including those in Santa Cruz—employing surfboards as standard equipment for their rescue units.

By the end of the decade, Duke gave up on his Tinseltown dreams and returned to Hawaii. In 1932, he was elected Sheriff of Honolulu—a position that he held until 1961—and which allowed him to tour the world as an ambassador of the aquatic arts. He remained a master waterman until the time of his death in 1968, a beloved and revered figure worldwide.

His 1938 sojourn to Santa Cruz, however, would be his third and last. In advance of his visit, Skip Littlefield, his pal from the Boardwalk, penned a profile in his honor. “Other champions have come and gone and their fame has most generally been forgotten,” Littlefield wrote. “But to the youth of many generations the name and greatness of Duke Kahanamoku is like the surging seas off his own paradise isle—never ceasing and never ending.”

Special thanks to Kim Stoner and Barney Langner for supportive research on this article.

That was a super read. I’ll bet the Duke remained noble even though he was under pressure from travel and performance schedules.

Geoffrey,

I really loved and appreciated this “piece”. I learned so much that I was never aware of. I’m glad to have spent a lot of time in the “plunge” myself and now know the Duke was a star swimmer there before I jumped into those salty and mysterious waters. Isn’t Santa Cruz history special! Thanks for this superb article. David