In 1942, the U.S. and Mexico hammered out a deal that allowed millions of Mexican men to enter the country to work.

Through its 22-year history, the Bracero Program saw more than four million workers come to work as agricultural laborers. The Braceros—which means people who work with their arms—faced harsh conditions, discrimination and low wages.

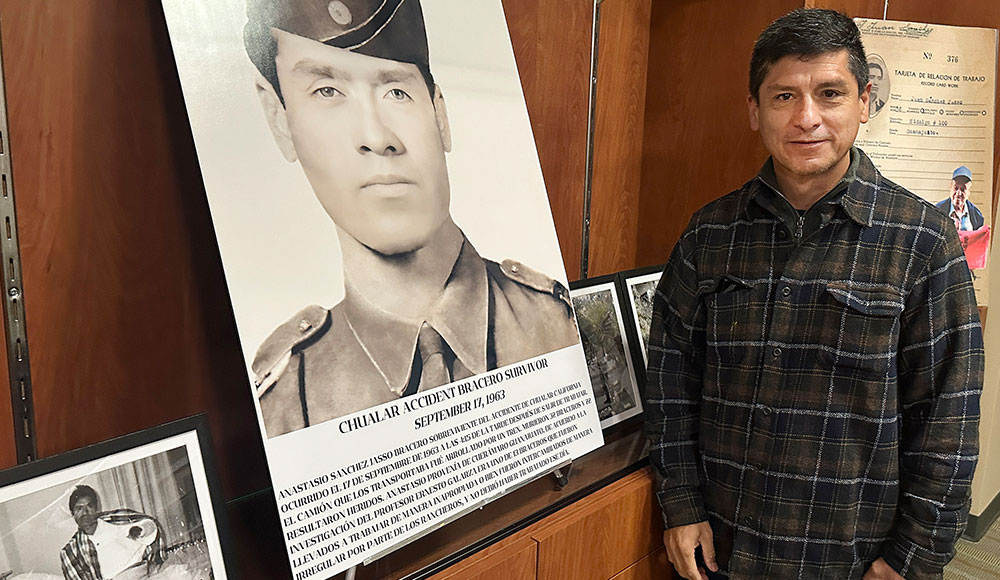

But more than that, their work and struggles helped shape the rich history of the state’s agricultural industry, says Jose Sanchez Vargas, who has created a historical display of Bracero history.

“This is the work of my life,” he says. “By doing this I’m making sure the legacy and the sacrifices of my ancestors and all immigrants who have come before us are recognized and valued.”

Called “Braceros Hasta el Último Aliento” (Braceros Until the Last Breath), the display will be available through Feb. 28 at Watsonville Public Library’s main branch.

It is told through the stories of three Braceros who were alive at the time of the research: Arnulfo Palomino Alvarado, Jesús Solís Navarro and Javier Castro Arce.

From June of 1951 to April of 1952 there were close to 20,000 Braceros from the state of Guanajuato, 50% of whom went to California to work in Modesto, Fresno, Tulare, Yolo, Salinas, Monterey and Santa Cruz, Sanchez says.

They ranged in age from 19 to 50, and paid around 100 pesos for the ticket by train and about 60 pesos by bus.

Sanchez lived in Watsonville from 1986 to 2005, and says he formerly worked as a lettuce picker. He now lives in Guanajuato, Mexico.

In one interview conducted for the project, a man told me he had never seen one ‘gringo’ in 25 years working in the fields .

“To discover this information is very important to me, and we need to let the world know of the sacrifices they made. These people came here to rescue the American economy,” Sanchez said.

Sanchez explained how the U.S. lacked people who would work in the fields as the country recovered from the economic fallout of World War II.

“They came here not to take away American jobs,” he said. “The U.S required them here to rescue the economy after World War II and to help get the country back on its feet.”

In making the display, Sanchez says he wants to preserve the history and legacy of the Braceros of his home state, Guanajuato.

This includes his uncle Anastacio Sanchez Jasso, who was one of 22 who survived when a train hit the bus transporting them to work in Chualar, California. But 32 died in the crash on Sept. 17, 1963.

That incident was not the only one in which Braceros were injured, and the culture that allowed this to occur—and the stories of the people affected—should not be forgotten, Sanchez says.

Arnulfo Palomino Alvarado was 21 when he left his wife and daughters to come pick lettuce. He used the short-handled hoe, which the California Supreme Court banned in 1975.

“It is important to tell their histories because each one of them has a journey of struggles, sacrifices and most of the time people do not know about it or they are forgotten, they are blamed and used as scapegoats in many instances especially in politics,” he says. “In this time of darkness with the new government, we must step out to protect them, to legislate in their favor so that they can live with no fear.”

Sanchez graduated from Cabrillo College with an AS degree. He was an activist with the Watsonville Brown Berets. He is part of the White Hawk Indian Council for children, and is part of a Coalition of Immigrants from Guanajuato, which helps immigrants in both the US and Mexico with their needs.

If Todd Guild is so concerned about oppression & racism, he could detail today’s ongoing genocide of Palestinians by the terrorist theocracy of Israel.

But that doesn’t serve the relentless anti-White agenda of the woke media — so let’s just keep hammering away at White guilt from centuries gone by.

with the impending cease fire and end of hostilities this coming Sunday, let us hope that those who care about all the residents of Gaza and middle east will work together to bring back a region which has been largely destroyed by racism, religious bigotry, economic greed and pure ego (witness Al Assad and Netanyahu).