In 1985, Paula Hernandez worked at Richard Shaw Frozen Foods in Watsonville, processing spinach, broccoli, cauliflower and other vegetables, depending on the season.

It was a steady, albeit physically demanding job that allowed her to support her family at a time when the city was home to several frozen food plants, earning the area the title “The frozen food capital of the world.”

“It was good,” Hernandez says. “The only thing we didn’t like is they never opened job opportunities for line workers.”

Instead, management advertised higher-level jobs in local newspapers, she says. That was not the only source of discontent. During this era, industry leaders and politicians engaged in union-busting, which still affects labor. Perhaps the best example occurred in August 1981, when 11,000 air traffic controllers—represented by the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Association—went on strike to protest unfair wages.

In a speech from the Rose Garden, then-President Ronald Reagan demanded that they (air traffic controllers) go back to work—two days later, all those who hadn’t returned were fired. The unilateral move showed workers and industry leaders where government loyalty lay.

When the owners of two Watsonville plants—Shaw and Watsonville Canning and Frozen Food—proposed cuts to already abysmal pay and family health benefits, a thousand workers, including Hernandez, walked away from their jobs and embarked on a strike that’s considered a watershed moment in United States labor history. In many ways, the strike was successful.

Historian and Stanford University lecturer Ignacio Ornelas says the workers—most Latina women—took unprecedented leadership roles in the strike.

“It was a very powerful moment in United States labor history that often goes unrecognized,” Ornelas says.

The women occupied the picket line daily while raising children, maintaining their households and navigating a union dominated by an entrenched, good-old-boy network.

“In the history of labor movements, many of them are led by men,” Ornelas explains. “But in this case, the iconic leaders at the forefront were Mexican-immigrant women, in many cases undocumented. They fought really hard to gain some of those victories.”

And this grit, which translates to ganas in Spanish, did more than make the strike victorious. It also inspired a new generation of Latino leaders who hold leadership positions today.

Paula Hernandez’s son Felipe went on to be elected to the Watsonville City Council and serve as the mayor of Watsonville; he also served on the Cabrillo College Board of Trustees and sits on the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors.

“I’m finding their parents and grandparents have this really beautiful history, obviously as immigrants, but like her, the very hardworking ethic that they live by has been transferred over to some of their children,” Ornelas says.

The greatest thing the women strikers could do, Paula says, is show future generations that Watsonville mothers have always been strong and would stand up to defend their families against injustice.

“We mingled, and we bonded,” Paula says. “We got stronger. We knew how we felt weak, but when we united, we became one. We were in the same plight, and we became mother strong.”

Felipe was about 10 when he accompanied his mother in the picket line.

“For me, it was watching her do different things—going down to the Teamsters Hall on Fifth Street, talking to the Teamsters, watching all the women there congregate and meet and discuss what they wanted to do,” Felipe says.

He remembers seeing his mother intercept a frozen food truck pulling into a grocery store’s parking lot and convince him not to drop it off. Instead, Felipe said that the driver left the load by the side of the road in a show of solidarity with the strikers.

“I thought, ‘Wow, my mom just told this truck driver, don’t bring the food,’” he says. “I admired my mom, and it left an impression on me. I was proud of her and everything she did.”

WAGE WAR

At the time, the workers were represented by Teamsters Local 912. Richard King, the secretary-treasurer and principal officer then, had negotiated a master contract with all the frozen food companies, giving all workers the same wages.

But buoyed by the anti-union sentiment that marked the era, Watsonville Canning owner Edward “Mort” Console forced a strike by slashing wages by 40 cents and taking away family health benefits.

Console was banking on a rule that allowed decertification of a union after one year of striking, thus allowing him to set the wages.

Console hired Littler, Mendelson, Fastiff and Tichy, a law firm specializing in employment and labor law, to assist with his efforts. He also got an $18 million line of credit from Wells Fargo Bank to get his company through the strike.

“In other words, the strike became a weapon of the company rather than a weapon of the workers,” says Joe Fahey, a rank-and-file activist with Teamsters Local 912—who later became its president.

Soon after Console made his announcement, Shaw announced he was imposing identical reductions at his company—Paula says Shaw refused to open its books to justify the proposal.

“We saw that the management had new cars and was always having parties in the conference room,” she says. “We weren’t getting equal opportunities. I thought it was very unfair what they were proposing. And they didn’t even show why they wanted it. They just thought we would fall into it.”

But the workers weren’t counting on their union—King was considered an ineffective leader. So, looking to fill this vacuum, the union looked to its rank-and-file members for strong leaders, forming a Strikers’ Committee.

Gloria Betancourt, an outspoken activist at Watsonville Canning for over two decades, became the face of the strikes. Paula turned down an offer to become a shop steward to whom other workers would bring their concerns.

“I was already stressing out with what was going to happen,” Paula says.

Shaw caught wind of her refusal and asked her to become a rank-and-file representative who would attend union meetings and report back to management.

“He thought I would be an ally to the company,” Paula says. “I was very outspoken and assertive about what’s going on.”

The Teamsters went into negotiations with the companies, which proved to be unfruitful, and Paula’s fellow workers came to her for advice.

“I said, ‘They’re taking away our health benefits. I’m for a strike,’” Hernandez confirms.

The workers at both plants voted to strike and began receiving $55 per week from the union fund. A food committee that funneled millions of dollars of food donations throughout northern California was also formed.

In addition, strikers received a weekly box of food from Second Harvest Food Bank and clothes for their families donated from local stores. Local grocery stores contributed soon-to-expire food, and bakeries provided pastries for the strikers’ breakfasts.

Paula says the show of community support kept the strikers going through the tough times.

“I didn’t feel the strike at that time because we were getting all this help,” she says.

After several weeks, the men left the strike for different jobs, saying they needed to support their families.

“I would go to the picket line and see nothing but women,” Paula recalls.

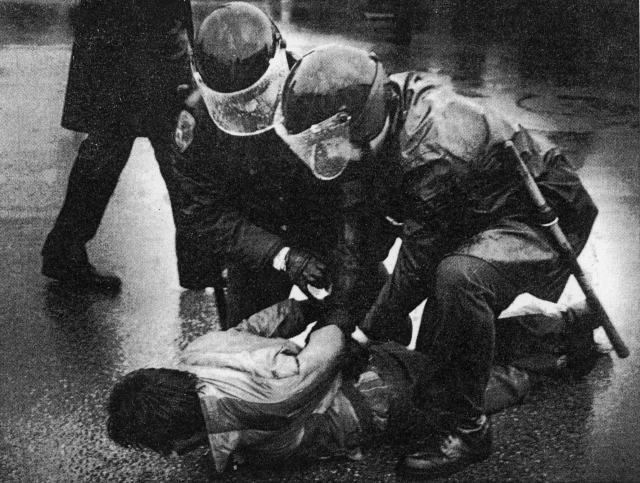

During the strike, union members found few allies in the city, which imposed rules for the demonstration so onerous that one striker was arrested for standing on her porch across the street from the plant.

According to Fahey, Shaw negotiated a settlement five months later, which reduced wages from $7.06 to $5.85 an hour. But Watsonville Cannery workers held out and continued the strike; there were also mass rallies, one of which turned violent when protestors began smashing windows on Main Street.

ENCROACHING DEADLINE

Under the National Labor Relations Act, strikebreakers were the only ones who could vote after 12 months on strike. If there were no workers to vote, the union could be decertified.

That was when the Teamsters learned something that would turn the tables: the union had never been formally approved by a majority membership vote at Watsonville Canning.

This meant that Teamster members would have to round up a thousand employees to vote for the approval, a Herculean task since many were no longer in the area.

They managed to pull it off, which restarted the clock and gave the union another year to strike.

Meanwhile, Console was facing troubles of his own: he had blown through his $18 million line of credit and had to mortgage his property.

In a case of poetic justice, the Teamsters had millions of dollars in accounts at Wells Fargo. And thanks to Console’s mortgages, the bank now owned his company.

With that as leverage, the union threatened to withdraw its money, which persuaded Wells Fargo to foreclose on Console.

David Gil, who Watsonville Canning reportedly owed $3.2 million, took over the company in 1987 and formed NorCal, according to a Feb. 11, 1987, article in the Register-Pajaronian.

That began a new chapter in the saga.

While NorCal offered the same wages as was in the contract with Watsonville Canning, the seasonal workers who made up much of the workforce were seen as new hires, meaning they would not qualify for health benefits for several years.

So, the strikers began a five-day hunger strike, which capped off when they marched on their knees from the plant to St. Patrick’s Church.

The strike was successful, and health benefits were restored.

“They were heroic,” says Oscar Rios, a former Watsonville City Councilman who helped with the strikes. “They were the ones that came to the forefront, and it was the women that organized the hunger strike. They saw they had the strength and the power to make this happen.”

A BETTER TOMORROW

Rios says the strikes—and the people who worked in the plants—effectively shaped the evolution of the South County city.

“The reason gentrification has not happened is because many of the homes were purchased by cannery workers,” Rios says.

While the outcome was not everything the workers wanted, Fahey says it did have some significant achievements.

“Leadership,” Fahey says. “There were just tons and tons and tons of people like Paula Hernandez who stepped up and took leadership of their coworkers. That spread in the community, so there was a real sense of “Watsonville is an important place.”

Ornelas says that the women stand out in history for the way they bucked the system, despite poor treatment by both their companies and their union.

“They really saw past the cronyism between the union and the corporations,” he says.

But Ornelas stops short of romanticizing this period in history. Throughout the strike, they still had to contend with the same day-to-day struggles everyone faced.

“It was a very painful period,” he says. “People went hungry. People were evicted from homes. Their properties were foreclosed. People lost their jobs. But through it all, the women showed that there was a reason to fight; there was dignity to fighting.”

For Paula, the victories did not end there. She persuaded management to let her move up the ranks to become a foreman.

With that under her belt, she paved the way for her fellow workers to be promoted. Paula also convinced the company that women could be forklift drivers; if they could drive a standard transmission car, she told the women that learning a forklift would be easy.

I said, “We’re going to train you, and you’re going to learn. And we’re going to learn it better,” she adds. “We were able to get six women as forklift drivers.”

That, she says, created an industry-wide change.

“We got our own women, and that’s what created this whole change there,” she says. “And productivity went up because us women were better at it. We looked at something and said, ‘This could be changed. We could do this.’”

Monterey County Supervisor Luis Alejo, who also served as a California Assemblyman and as Watsonville Mayor, says the sight of the women picketing on Walker Street inspired him.

“The Watsonville Cannery Strikes left a lasting impression on me since then about standing up for what’s right and never backing down,” he says. “The strikes have become symbolic, and even synonymous, of the hardworking people of Watsonville.”

Alejo says he studied the cannery strikes closely as a student at UC Berkeley.

“Because it was the history of our courageous mothers who never crossed the picket line on each other for two long and difficult years,” he says. “They were a symbol of strength and pride for me. I remember proudly seeing the numerous photographs in Elizabeth Martinez’s book, 500 Years of Chicano History.”

In statements when he was sworn in as County Supervisor in January, Felipe Hernandez was quick to credit his mother as his inspiration.

“For me, something special occurred during that time,” he says. “It was a tumultuous time, but something special occurred amongst the women. I learned life lessons. I think, both leadership and to stand up to injustice.”

Love learning about this history, especially as someone born long after the strikes in Watsonville–thank you for the thorough article!

Wendy and I had been teachers in town for several years and were disappointed to see working families treated badly and know of the negative impacts on the community. But at the same time we were encouraged by the solidarity and bonding that took place and the mutual support that permeated the town.

The dedication and hard work of mothers shapes the valley in the most powerful of ways.