While attending college in Santa Cruz, UCSC alum Noa Lewin took a special interest in portrayals of autism in the media.

The issue is a personal one for Lewin, who graduated in 2018 and goes by the gender-neutral pronoun “they.” Lewin is on the autism spectrum.

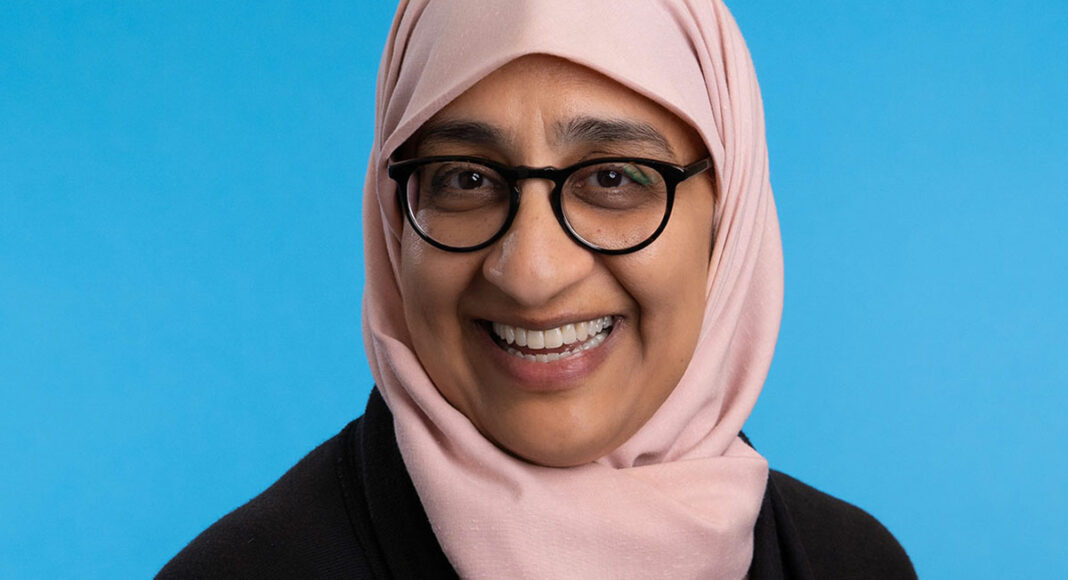

While at UCSC, Lewin approached developmental psychology professor Nameera Akhtar during office hours for a discussion about language. As Lewin was getting ready to leave, they mentioned to Akhtar the experience of being on the autism spectrum, which opened up another discussion, and the two chatted for a while longer.

A few months later, Lewin approached Akhtar about the possibility of collaborating on a research project, and Akhtar agreed to be Lewin’s senior thesis advisor. For the project, Lewin looked at 10 years’ worth of Washington Post articles, specifically stories that mentioned the word “autism,” “autistic,” or “Asperger’s”—the latter being the term for the syndrome on the milder end of the autism spectrum. From that stack, Lewin weeded out a few articles that barely discussed autism or Asperger’s at all. After that, Lewin ended up with 315 articles on the topic from 2007 to 2017.

Akhtar says she and Lewin chose to focus on the Washington Post partly because the paper is read by policymakers in Washington D.C. “It’s influential in multiple ways,” she says.

While combing through the articles, Lewin looked for a number of markers, including instances of “deficit perspectives,” the notion that autistic people are inherently disadvantaged or abnormal, as well as examples of “neurodiversity.” The concept of neurodiversity focuses on being open to different ways of thinking. “There are different strengths and different challenges associated with different brains,” Akhtar says.

Lewin and Akhtar say that, rather than focusing on pathologizing people who think differently, society should work to be accommodating to those who bring different perspectives. Lewin and Akhtar found slight improvements in how autistic people were portrayed in Washington Post stories, with more examples of acceptance and neurodiversity as the years went on.

“Things are moving in a much more positive direction, and it can especially have a positive impact on the lives of autistic people,” Akhtar says.

Lewin feels “cautiously optimistic” about the findings, which appear in the new online edition of Disability and Society. Like Akhtar, Lewin says there’s room for improvement in news coverage. Lewin and Akhtar both stress that stories about autism often include quotes from clinical or research-minded experts, while leaving out the perspectives of those who actually have autism themselves.

Lewin says, for example, that they seldom see non-speaking autistic individuals quoted in stories about non-verbal autism, even though many of them are able to speak via email or by using other communication devices.

Lewin adds that perhaps more non-speaking autistic individuals would develop advanced ways of communicating if they were given tools to help them communicate their needs at a young age—right after being diagnosed, for instance—instead of having adults spend the early portion of a child’s youth lamenting that the kid isn’t like everyone else.

“It’s all done in good intention, but a lot of those things really do a lot more harm than good,” Lewin says. “The psychological impact that can have on a kid is not talked about enough in education or in medicine. The person wants the help, but there are problems with the way it’s being done.”

UPDATE May 21, 12:15pm: A previous version of this story contained one pronoun error.