By Cathy Kelly

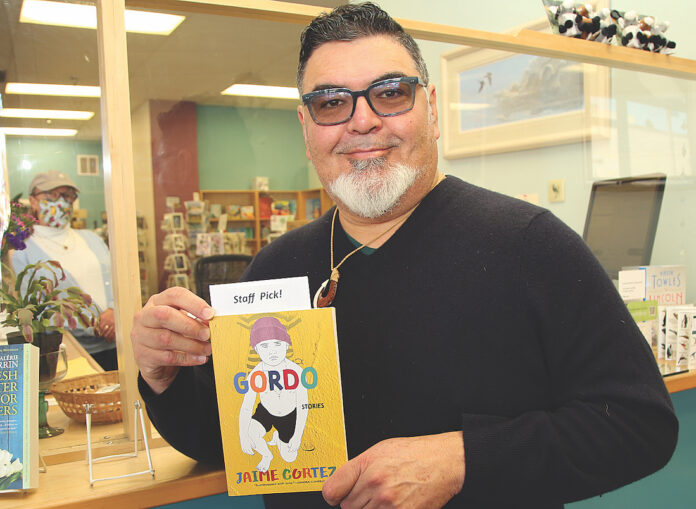

WATSONVILLE—Local author Jaime Cortez always had nicknames, and now one of them has become his first book. “Gordo,” a paperback collection of stories, is quickly gathering praise after its release by a national publisher in August.

And while “Gordo” is Cortez’s first widely distributed work, the 56-year-old has a significant history of illustrating and writing to illuminate causes such as sexuality, social justice and Chicano identity.

The semi-autobiographical stories of “Gordo” stem from Cortez’s early life in a San Juan Bautista migrant field worker camp and then in Watsonville. They are humorous, humble and heartbreaking, and they have garnered glowing reviews from NPR, The New York Times and others.

Booksellers say it is “flying off the shelves,” including at Kelly’s Books in Watsonville and at Bookshop Santa Cruz. Cortez says the book has already made its way onto several college reading lists, and that Grove Atlantic Press quickly ordered a second printing of the bright yellowish-gold paperback.

Cortez, who works for the Hewlett Foundation of Menlo Park, said the book’s reception surprised and delighted him. It also sent him traveling around to more than 30 new-book events in three months. The most recent was at the prestigious Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, and the next is an online Bookshop Santa Cruz event at 6pm on Dec. 9.

“I’m very thrilled with the positive response to the book,” he said, during a recent interview in Watsonville. “It’s just a lot to keep up with. I feel very blessed and very tired.”

Cortez was calm, soft-spoken and humble during the interview, though clearly pressed by his hectic schedule. An experienced and accomplished artist, he smoothly brings readers into the tight circle of his family and neighbors. Survivors, one wants to call them. Strong.

And like Gordo, their nicknames were not kind or subtle. One teen artist was called “Fat Cookie,” and a man who became a locally legendary hairstylist was termed “Raymundo the Fag.”

The tragicomedy is mindboggling, from the transgender next-door neighbor, Alex, who abuses his pretty young girlfriend from El Salvador to Fat Cookie, whose anger propels her art and her teenage flight from the camp, with her mother’s 22-year-old, Camaro-driving “creepy” boyfriend.

In one early story, set at the camp, Gordo and Fat Cookie argue about life. He is about 10, and she points out her five-year advantage, plus her great height and legitimate immigration status. Fat Cookie says she soon will be able to drive and “get the hell out of here.”

Gordo often seems to be around older people and doesn’t understand the hard truths that come from their mouths. When Fat Cookie rages obscenities about her mom, Gordo protests, saying her mom gave her life, “the greatest gift in the solar system.” Fat Cookie scoffs, before telling him he is “the only idiot I know who talks about the solar system.”

Cortez earned a bachelor’s degree at the University of Pennsylvania and a master of fine arts at UC Berkeley, where he also collected the Eisner Award for highest achievement in the humanities.

Cortez was in his 30s when he wrote down a few “Gordo” stories, he said, only wanting to share his childhood experiences somehow.

“They mattered to me, regardless of the audience,” he said.

That childhood included a tough, tequila-adoring dad who was a nicknaming pro. The elder Cortez, in one scene, termed a field supervisor with a thick neck and funny manner, “Head and Shoulders.” As young Gordo looked on, his dad’s nickname was met with howls of laughter from others in the camp.

But Cortez said his father got and stayed sober, right after his son left for college and later worked for years at Martinelli’s.

And responding to the common question, he said the stories with Gordo as the protagonist are about 80% true life. On the other hand, Cortez said the Raymundo the Fag story is a composite. It is a perfect-circle tale, in which Raymundo ends up forgivingly styling the hair of Mauricio ‘Shy Boy” Pardo, who had taken First Holy Communion with him, teased him in school with others in “the rough crowd,” and then was fatally shot in the head.

Gordo’s many touching passages and characters make for stories that fall in several literary categories, as the young, chubby, gay boy discovers all that growing up entails. He seems held tightly in his family and community, in a community outside the mainstream while being a kid outside that marginalized community.

But, these days, Cortez is wondering about a second offer from a publisher and fielding a few overtures from TV and movie producers.

One suspects it wasn’t an easy journey, and readers are warned of the emotional weight right at the book’s start, with a dedication to his parents. (His mom is kind, strong and stable in the book). Cortez writes, “I dedicate this book to Felicitas and Felipe Cortez. You loved me, you told stories, and you gave me an extended master course in gallows humor. I ask for nothing more.”