Writer, director and actor Steve “Spike” Wong remembers when he realized he wanted to tell stories.

He was about 5 years old and was riding the Jungle Cruise attraction at Disneyland with his parents. He managed, he says, to convince them that the animatronic hippopotamus on the ride was real.

“My parents never really shut down my imagination,” Wong says. “They just let me go with it.”

Wong was born in Watsonville in 1952 after his father’s parents had landed there as agricultural laborers and cannery workers. He graduated from Watsonville High School in 1970 before attending Cal State Chico as part of their honors English program. Eventually, he returned to his hometown to be a teacher at Watsonville High.

“When I was growing up in Watsonville, it was really small,” he says. “It was under 10,000 people. Pretty much every family was at least aware of other family groups. For me, that helped ground me into my community. Having those connections is why coming back to teach at Watsonville High made complete sense.”

Throughout his life, Wong has written, directed and acted in numerous plays, including one performed off-Broadway in New York. His latest work, White Sky, Falling Dragon, will open at the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts in just a few weeks.

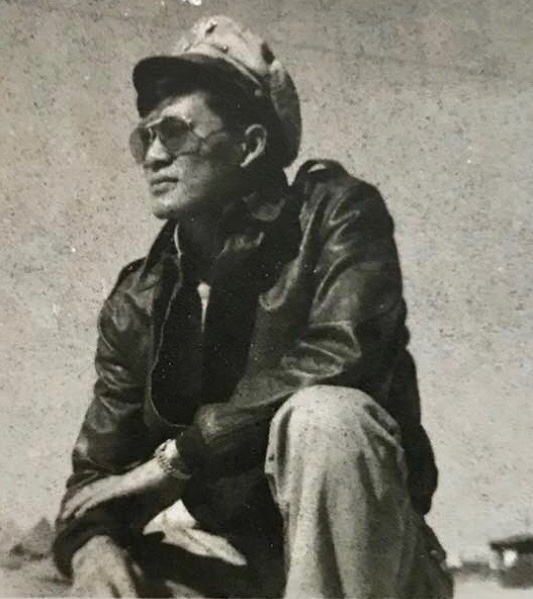

The story is inspired by Wong’s father, Captain Ernest Wong, following his struggles as he moves back to Watsonville after World War II. The young Cantonese man faces emotional challenges after a tragedy occurs during his last war mission. His cultural and familial obligations continually clash with his search to settle in America.

“The play takes factual reality from my father’s experience and then creates a sort of fictional storyline on top of that,” Wong explains. “The biggest surprise when I was writing this—I always thought, from the very beginning, that the hero of the story would be my grandfather. But it was my grandmother. When I was small, my mother was ill, and I spent time with my grandparents in a house on Lincoln Street. I think deep down, her strength has always been inside me. The way that has come out in this play—it’s powerful.”

Wong was a freshman at Chico when he wrote his first play. But it wasn’t until he was 55, when he visited China for the first time, he said, that things shifted.

“When I got to China, suddenly, everything that I’d kind of set aside in my life … all of that just sort of started speaking to me,” Wong says. “When I came back, I started writing more things about what I lost, growing up in a country that still today has racism against Asians.”

In 2016 Wong wrote Dragon Skin, which premiered at the 2018 Eight Tens @ 8 play festival in Santa Cruz. The one-person show covered 50 years of his life in just 10 minutes and subsequently played at the Marsh Theater in San Francisco.

At the premiere of Dragon Skin, Wong realized his work’s impact.

“On opening night during the reception, this strong, swarthy older guy walks up to me, puts his hand out to shake, and says, ‘Let me tell you something: I am Greek, and that play was my story,’” Wong says. “I realized you can write from your cultural background as truthfully as you can, and it becomes a universal, human story.”

The idea for White Sky, Falling Dragon came to Wong in 2017, when he was abroad in Barcelona, Spain.

“I suddenly heard my dad’s voice, walking into a home and greeting my grandmother,” he says. “I got my phone out and typed a line of dialogue. Suddenly, all this stuff started coming up.”

Wong strived to answer the question: What was it like for his father when he came home from the war?

“He’d been a target of racism,” he says. “The Chinese Exclusion Act was still in place when the war was going on. 20,000 Chinese signed up to fight for a country that would not let even their relatives in. He was torn: ‘I’m Chinese, but I need to be American if I want to stay here.’”

Wong funded White Sky, Falling Dragon himself and set out to find the right set designers, producer and an all-Asian cast. The play features live music with Chinese instruments and visual effects.

“It’s so specific to Cantonese Chinese Americans, in a small town, I couldn’t turn it over to someone else,” he says. “I had no board [of directors]. I had to take a leap of faith and say, ‘OK, I can do this.’ Early on, people came to me wanting to work on this project. The play was attracting people. But it wasn’t me they were looking at; it was the story, the humanity, the power behind it.”

Wong has “never been more motivated” on a project.

“It’s not just me,” he says. “It’s all my ancestors who helped get one person to this country. That person started everything. I am the result of what they dreamed about and worked for. In some essence, this play is all their doing. I’m just the vehicle.”

‘White Sky, Falling Dragon’ runs Aug. 26-27 and Sept. 1-4 at the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts. A complimentary reception will be held on the opening night following the performance. Tickets are available at mvcpa.com. More info at soaringdragon.net.

Our post WWII baby boomer Chinese American generation is coming to terms with family and identity issues so Steve Wong’s work is timely for contributing towards a critical mass of coming to terms with why and when our ancestors came “Longtime Californ”” and how each generation is impacting

the others. It is possible that a Wong, if it’s not a paper name, could be from the original four railroad villages in Toisan where recruits for the Central Pacific came from. It’s also possible that the Monterey Bay fishing villages were shut down by Italian and Portuguese competition which would have caused migration to agriculture in Watsonville and Salinas, Central and San Joaquin valleys, etc. The Chinese Exclusion Act from May 6, 1882 to December 17, 1943 has had concrete consequences on our southern Chinese families to this day and to the discrimination still faced by the AAPI community as a whole. WWII in the Pacific still reverberates in today’s US Indo-Pacific policy. I hope Steve can continue to support other playwrights with similar themes.